He’s not under arrest — but he sure could use a rest.

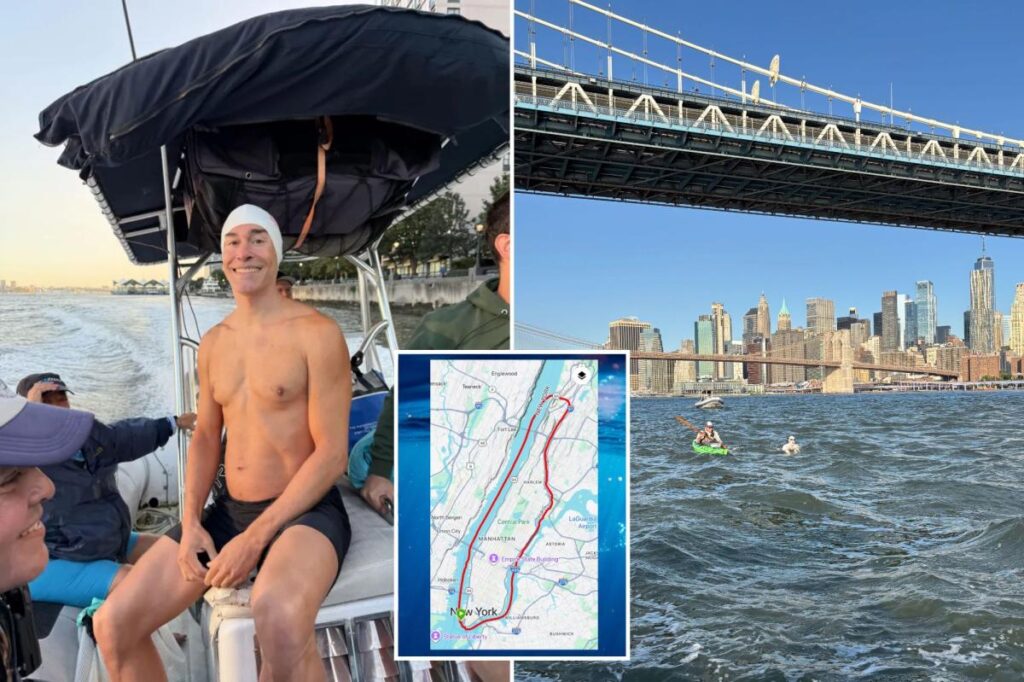

In September, 49-year-old New Yorker Michael Moreau jumped off the southern tip of Manhattan ‚Äî and didn‚Äôt emerge until he‚Äôd swum up the East River, through the Harlem and down the Hudson to complete the famed and formidable 28.5-mile loop.¬Ý

The (flutter) kicker: He did it all in handcuffs, and in well under 10 hours.¬Ý

Moreau’s felony-flavored feat earned him two Guinness World Records — one for completing the longest open-water swim in handcuffs, and one for becoming the first (and fastest) swimmer to circumnavigate the city’s waterways in shackles.

Why?¬Ý

‚ÄúWhy do anything?‚Äù Capri Djatiasmoro, a fellow marathon swimmer and member of Moreau‚Äôs support crew, asked. She conquered the same 20 Bridges Swim Around Manhattan¬Ý‚Äî albeit with the luxury of her limbs ‚Äî on her 63rd birthday in 2014, and said the rush of the open water feels as illicit as Moreau‚Äôs steel-strapped wrists symbolized.¬Ý

‚ÄúAfter I swim, I‚Äôm high as a kite,‚Äù Djatiasmoro, co-founder of Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimmers, said. ‚ÄúI guess normal people, nonswimmers, could relate it to the high after a great workout or incredible sex.‚Äù¬Ý

But Moreau’s moat-ivation wasn’t kink. It was part nautical nature, part unfinished business, part desire to probe the outer edges of merman mastery.

“When I started hearing these stories about people who had not given up on the opportunity to really test the limits, I thought, ‘Why can’t I do this thing?’ That was the beginning of my journey of trying to figure out how I was gonna realize my potential,” he said. “And I knew I needed to do it in the water.”

Born to swim¬Ý

Moreau, a creative director on land, has long been a fish in the water.¬Ý

“According to my parents, I could swim before I could walk,” he said. “I pretty much told them, before I could even speak, that my desire was to be in the water. That’s what I was made to do and where I was made to thrive.”

Moreau made waves as a high school and college swimmer, winning national championships and setting at least one record that still stands today. But he eventually hung up his goggles ‚Äî and didn‚Äôt pick them up for the better part of 20 years.¬Ý

Then, in his mid-40s, the water called. Freestyle phenoms like Diana Nyad and Ross Edgley seeped into his social feeds. He couldn‚Äôt shake the feeling there was more in the tank.¬Ý

“The first thing that went through my head is … that’s wild. Why would you even do anything like that?”

Michael Moreau

The challenge? Setting a goal that didn‚Äôt feel like a victory lap of his youth. The solution?¬ÝUltramarathon open-water swimming, or generally any non-pool, nonstop outdoor swim over 10 kilometers.¬Ý

That‚Äôs more than 430 lengths of a standard 25-yard pool ‚Äî plus the uncontrollable currents, conditions and creatures of the natural world. Add in logistics like coordinating boat traffic, reading tides and securing a skilled crew for safety and support, and the prospect requires the kind of mental and physical prowess elite lap swimmers rarely hone.¬Ý

“I thought, ‘This is uncharted territory for me. This is something that I feel like I need to pursue,’” Moreau said. “And I kind of went out at full force.”

He hired a coach, put his social life on ice and set his sights on one of the most treacherous, choppy and marine-life-laden open-water conquests: Hawaii‚Äôs Molokai Channel swim, a 42-kilometer deep-ocean course with only about 100 finishers to date.¬Ý

Moreau became one of them in 2024, stroking through the night in 13 hours and 11 minutes ‚Äî the 14th fastest time in history. He surfaced still thirsty.¬Ý

‚ÄúI wonder if there‚Äôs something a little bit off the beaten path that is a little bit more controversial,‚Äô‚Äù Moreau thought. There was: handcuffs. The jailbird jangles had restricted Egyptian pro swimmer Shehab Allam‚Äòs wrists in 2022. His record-holding 11.6 kilometers was the distance to beat.¬Ý

“The first thing that went through my head is the same thing that I think goes through a lot of people’s heads: That’s wild. Why would you even do anything like that?” Moreau said.

But the next thing that went through his head was an aquatic equation he became determined to solve: If up to 90% of a swimmer‚Äôs propulsion comes from their arms, how does one swim when their hands are tied? ‚ÄúThen to me,‚Äù Moreau said, ‚Äúit became more of a technical challenge.‚Äù¬Ý

The best way to crack it, he deduced, was to lean on his historically strong breaststroke kick. And the best stage on which to attempt it, his logic later went, was the best city in the world.¬Ý

So after sailing past Allam’s record by returning to Hawaii in handcuffs in May 2025, Moreau set out, yet again, to do what no man had done before: swim the city’s perimeter in a literal bind. “If I’m able to pull this off,” he thought, “this will be the defining moment of my open-water career.”

“Nonswimmers don’t want to hear about it because they go, ‘Oh my God, you swim in the Hudson River?’ I wouldn’t stick my finger in there.”

Capri Djatiasmoro

Swimming upstream¬Ý

Like members of any sporting subculture, plenty of open-water swimmers pursue maniacal-to-mortals exploits that fly under the mainstream radar.¬Ý

In New York, enthusiasts embark on annual Urban Swim adventures like circling the Statue of Liberty or front-crawling beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. About a hundred people pay $5,500 to take on the 20 Bridges Swim Around Manhattan, just one-third of the so-called ‚ÄúTriple Crown‚Äù of open-water swimming. And if the only thing a lap around the Big Apple wets is an athlete‚Äôs appetite for more, they can do it all over again and loop the city twice.¬Ý

Then there are the superhuman stunts, like reverse-swimming around Manhattan — that is, against the currents — and powering around the island in butterfly. Just last year, a local therapist and artist became the first to swim around the borough — and then run around it too.

‚ÄúNonswimmers don‚Äôt want to hear about it because they go, ‚ÄòOh my God, you swim in the Hudson River?‚Äô I wouldn‚Äôt stick my finger in there,‚Äô‚Äù Djatiasmoro said.¬Ý

But since the early 2000s, she’s helped organize swims like a 10-miler from Coney Island to Red Hook, and has only once been whacked by a seal, sturgeon or something else lurking in the great unknown. “It was very funny,” Djatiasmoro recalled. “I just kept swimming. That was it — one smack.”

Yet even she was alarmed by Moreau‚Äôs proposition to take on the city‚Äôs seas in chains. With limited arm mobility, how would a crew swiftly hoist him, if necessary, out of harm‚Äôs way? ‚ÄúHe mentioned handcuffs,‚Äù Djatiasmoro recalled, ‚ÄúAnd I said, ‚ÄòWow. Good luck with that.‚Äô‚Äù¬Ý

Swimming a marathon distance in handcuffs requires ‚Äúan adaptation to remove one of the biggest elements that can support you in any swim, which is the hands, and put all the focus and the efforts on your legs and lower body,‚Äù the former record holder Allam, 35, told The Post. He commended Moreau‚Äôs effort, adding that he expected his record to one day be broken.¬Ý

“I know how much effort it takes to be achieved, maybe more than anyone,” Allam said.

Locked up and locked in¬Ý

Moreau wasn’t deterred. He moved apartments to access a 25-yard, 24-hour pool. He trained in rough conditions off of Coney Island, fueled by the liquid carbs stashed in the buoy that trailed behind.

At his peak, Moreau racked up weekly distances nearing 65,000 yards, or 37 miles. He did it all with restricted wrists and without leaving his demanding day job.¬Ý

‚ÄúI‚Äôm training in a pool with a silicone ring tied around my arms and everybody is thinking I‚Äôm doing this weird drill,‚Äù he said. ‚ÄúThere‚Äôs a lot of second-guessing. There‚Äôs a lot of self-doubt. There‚Äôs a lot of: Is this even worth the trouble?‚Äù¬Ý

But the more Moreau practiced, the more he bolstered his body and mind. He repeated visualization exercises and came to trust that the most mentally paralyzing dangers — from motorboats and sharks to dead bodies and deadly bacterias — were more rare than common.

‚ÄúYou eventually learn how to adapt yourself out of that mindset and realize what you need to focus on is your swimming, how you‚Äôre handling the waves, how you‚Äôre handling the currents, your breathing,‚Äù Moreau said. ‚ÄúYou try to manage everything that is in your control.‚Äù¬Ý

Then, on the morning of Sept. 9, 2025, Moreau locked up and jumped in. His crew ‚Äî including Djatiasmoro, his sister, a boat captain, a kayaker and a Guinness World Records officiator ‚Äî coasted by his side.¬Ý

‚ÄúI was euphoric,‚Äù Moreau said when he reached Hell Gate, a tumultuous mix of three tributaries near Randall‚Äôs island, well before the required time. But his elation didn‚Äôt last. Turning onto the shallow, disorienting and reverse-flow waters of the Harlem felt like hitting a ‚Äúbrick wall,‚Äù Moreau said.¬Ý

Even kicking down the Hudson ‚Äî considered the ‚Äúhome stretch‚Äù with over 12 miles to go and the Statue of Liberty in view ‚Äî presented a perilous twist: Construction on the Lincoln Tunnel had created a current that threatened to pull him straight under a barge. ‚ÄúI had no idea until after the swim‚Ķhow dire that situation was,‚Äù Moreau said.¬Ý

(Jail) breaking 10¬Ý

Nearing Brookfield Place, Moreau‚Äôs kayaker relayed thrilling news: If he hustled, he could break 10 hours. Most unshackled 20 Bridges swimmers finish in seven and a half to nine and a half hours; Moreau‚Äôs goal was 11.¬Ý¬Ý

“Hell yeah, let’s do this,” he thought. When his sprint-kick to the finish clocked a 9 hour and 41 minute time, Moreau said he “let it all out.”

‚ÄúIt was the culmination of everything that led up to it ‚Äî the uncertainty, the amount of doubt in my mind about: Have I gone past even what is humanly possible?‚Äù he said. ‚ÄúTo have that far-fetched pipe dream ‚Äî where literally everybody is telling me, ‚ÄòYou‚Äôve gone too far, this is madness at this point‚Äô‚Äô ‚Äî¬Ý finally crystallized into reality‚Ķwas monumental.‚Äù

Looking back, the triumph left Moreau with more than two Guinness World Record plaques and one case of cellulitis, a painful but treatable bacterial infection, in both legs. ‚ÄúThis is really a testament that there‚Äôs no limit to how big you can dream,‚Äù he said. ‚ÄúYou should never stop doing that.‚Äù¬Ý

As for his next big dream? ‚ÄúIt may be too early to say.‚Äù¬Ý

Read the full article here