I remember my father leaving. He walked purposefully, hurriedly through the house. He was carrying bags. My mother was crying, and he walked down the side of the house and away.

I remember it being a shock. Other than that, I can’t remember what I felt. But after it happened, I didn’t tell anyone. I didn’t tell my friends, not even my best friend, not for a year, and even then, he found out some other way. He was furious with me. But I was deeply ashamed and could not have imagined telling anyone.

Why? Part of this was the time. Divorce was not so common – or, rather, it did not feel like it was. There was still a furtiveness about it. But alongside this sense of shame, which I am sure many children felt, lay a feeling I have already mentioned, of not belonging. It was not that I had an unhappy time at school; I had good friends, I did well, I would even say that I was happy.

But I was there on a scholarship, and I was always aware that the boys around me came from richer families. They had large, beautiful houses, they took holidays to the same spots on the coast, ate at famous restaurants. I observed, with greedy fascination, their attitudes to money. I remember one boy being careful with what he spent at recess, even though he lived in a fancy house – and I remember thinking, ah, this isn’t something rich people do because they’re rich. This is why they’re rich – they manage money differently.

Labor’s desire for long-term government is the major lesson drawn from the painful Rudd-Gillard years.Credit: Nathan Perri

This isn’t true, of course. Rich people are as varied in their habits with money as anyone else; the idea they are cleverly frugal is self-serving mythology that feeds the idea that they deserve what they have. But while I know this, there is another part of me that still believes that old tale, just as there is a part of me who is still that boy who does not have as much money as those around him. But because I went to that school, I have never felt entirely out of place with the rich. Instead, I can mix with them; I can mimic their manners, more or less, behave in the right ways. But the most interesting (and perhaps damning) thing is that I am proud of this. I am proud of my ability to pass. Why?

Writing this now helps me make sense of my coming to work for the Labor Party. This desire to pass, as it turns out, has long been a part of Labor culture – and of labour parties around the world. The UK’s Labour Party first held government in 1924. Political historian Malcolm Petrie, reviewing books dealing with that first effort, writes: “Labour entered office determined to disprove accusations of extremism and to show that it was a respectable party.”

This was, in part, about rejecting the accusation, voiced most bluntly by Winston Churchill in 1920 when he was still a Liberal, that Labour wasn’t fit to govern. This explains the composition of the cabinet, and Labour ministers’ willingness to appear in court dress, despite the unease this provoked on the political left. It is also the reason some of the party’s most prominent policies were discarded as soon as it became clear that Labour could form a government. This was not only about electoral success. Its members went further, even dressing the part of more “respectable” MPs. There is something psychological and emotional going on here: a deep-seated concern about inferiority, coupled with a defensive determination to prove doubters wrong.

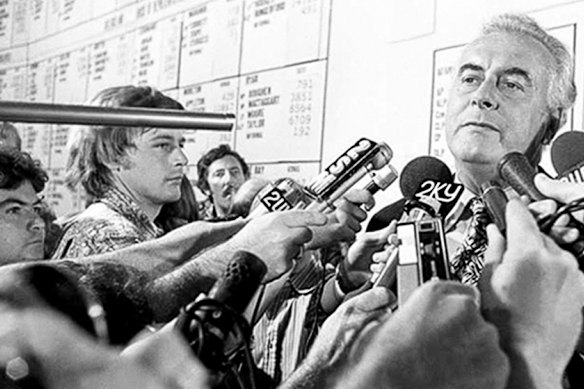

Forty years ago, then NSW premier Neville Wran pointed to a strange contradiction. The ALP, he wrote, is one of the oldest political parties in the world; it has governed often, including in crisis, and has many achievements.

Yet – and this is the great paradox – this tremendous Australian institution is still deemed in certain circles to be on trial, as it were, as to its loyalty. There can be no complete explanation of the destruction of the Whitlam government in 1975 without reference to this enduring paradox and its powerful effect on Australian political life for at least 65 years.

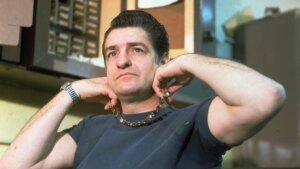

Labor suffers from a strong sense that it must prove its legitimacy. The downfall of Gough Whitlam plays into that.

Wran’s point comes down to a question of legitimacy: that in some way Labor, whenever it governs, is perceived by many as an interloper. If that sounds like ancient history, consider the more recent experience of the Rudd-Gillard government. Both prime ministers were subjected to campaigns of extreme aggression. Rudd was attacked by business over his mining tax, in the most savage display of corporate ferocity in decades. During Gillard’s time in power, the Murdoch papers, which had seemed already to have reached a frenzy, became still more extreme, abetted by misogynistic attacks and an emboldened business lobby. Gillard’s minority government was routinely described as “illegitimate”.

When Albanese, who was a senior minister and then deputy prime minister in those governments, talks about wanting Labor to be the “natural party of government”, this is the history he is pushing back against. More than that, it is the constant sense that Labor is somehow inadequate. It is, perhaps, not just a perception but a feeling he is trying to expunge.

This may be why defeat stings Labor so badly. It is not only failure, which is demoralising enough; not only the lost chance to do more of what the party thinks is good, to stop its opponents from doing what it thinks is bad. When the Liberals lose, they know in their bones they will be back: that is their destiny. When MPs from a Labor government lose, rejected by the people, it is as though they have been told, again, that they are not up to the job, that they don’t belong, that they have failed in their attempt to pass as people who know how to govern. Once upon a time, this was a matter of class. It has been many years since Labor ranks were dominated by the working classes – but then, feelings have little to do with logic.

Loading

This might help explain one of the remarkable features of the modern Labor Party: how quickly and brutally it disposes of its heroes. After Gough Whitlam’s fall, political journalist Paul Kelly has written, the party devoted itself to two tasks: avoiding Whitlam’s economic failure and matching the ruthlessness of Malcolm Fraser. After Keating went, Don Watson wrote, the party ran up “a new flag and will sail anywhere including the doldrums or over the horizon and out of sight to steer clear of the recent past. The new imperative is – do nothing that might remind the people of Keating.” More recently, Labor has done everything it can to make sure voters know this new era is nothing like the Rudd-Gillard era.

I understand that sense of shame; of being part of what was perceived by many, in its immediate aftermath, as a failure. I spent years attacking myself for the mistakes I had made as a Labor staffer, the things I had and had not done. So I well understand why, given the chance to redo history, to take another path, Labor wants to try it.

In fact, the best way to understand the approach of the Albanese government may be as a reaction to the Rudd-Gillard experience. The gradualism comes from the desire for long-term government; and the desire for long-term government is the major lesson drawn from the Rudd-Gillard years.

If you don’t have a long-term government, the argument runs, you cannot guarantee policies will stick. In 2023, Albanese told party members, “We know what we have begun can be undone unless we are there to protect it”.

The argument makes intuitive sense. But does it hold up? There are two objections. The first is that this idea of “embedding” policy depends on passing legislation and letting it become part of the landscape. But this would seem to depend on passing it early, and we are now almost four years into the life of this government.

Julia Gillard’s NDIS remains although her government was short-lived.Credit: Jason South

The other objection is stronger still. Which policies of the Rudd-Gillard years, exactly, were lost, outside of the carbon price? In fact, much of the Albanese government’s time has been spent doing further work on the policies of Rudd and Gillard: the NDIS, the NBN, the Gonski education reforms.

The fact this government is in substantive respects a continuation of that one suggests that you can deliver a significant number of enduring policies in a short time, as long as they’re good policies. Medicare is given as the major parable for the importance of long-term government. Medicare was introduced by Whitlam (as “Medibank”), effectively torn down by Malcolm Fraser, then revived by Bob Hawke, returned from the Whitlam years. Again, we come to the conclusion: the ideas matter at least as much, if not more. But ideas can get you into trouble. And trouble is the very last thing this government wants.

It is not unreasonable to have lived through the Rudd-Gillard years and drawn the conclusion that to change the balance of power in society you must proceed slowly, carefully, cleverly. But it is hard not to wonder, sometimes, if this government has learnt the lesson a little too well. To wonder whether – because the lesson comes with helpings of shame and sadness the MPs who lived through that time, who dominate the cabinet, go too far out of their way to avoid the slightest hint of anything that might remind them of those years.

‘When we say this government does not like conflict, this mostly means it does not want conflict with those who have assets.’

The most scarring of Labor’s battles in that era – apart from the internal ones – were with business. So it would make sense if you discovered, in the Albanese government’s aversion to conflict, a pattern of avoiding fights with business in particular. Which you do. Not, it should be said, in every case. Labor held its ground against the powerful Pharmacy Guild. Earlier this year, in one of his strongest statements of belief, Albanese made it clear he would not back down on industrial relations.

And yet the pattern is still striking. There are the concessions given by the government in its dealings with banks, supermarkets, gas and gaming companies. The habit is most jarring on climate policy. We export a staggering amount of fossil fuels; we are in the top five largest exporters in the world. This Labor government continues to subsidise the companies involved, giving away billions of dollars. In September, it gave approval to Woodside’s extension of the North West Shelf gas project until 2070 – 45 years from now. You could expand this line of inquiry further, to policies that don’t affect large businesses.

One of Labor’s most bruising battles was against the mining industry.Credit: AGE

In its first term, the government announced a new tax regime for those with large superannuation balances. The Senate wouldn’t pass it, so the government took it to the election. After the election, Labor had the numbers to pass its laws – but after pushback, most particularly from The Australian Financial Review and The Australian, it changed its policy in a substantial retreat. Again and again, it is those with assets who are protected. When we say this government does not like conflict, this mostly means it does not want conflict with those who have assets.

Labor’s task, historically, has been to change things on behalf of those who desperately need them to change. Albanese’s most common description of his government’s focus – holding nobody back and leaving nobody behind – is clearly Labor in its sentiments.

And yet, interestingly, we find the rhetoric is about what we must not allow to happen. There is, as so often with this government, a reluctance to state clearly, in sharp and positive language, what it wants to achieve.

Loading

This may be because the phrase itself holds a contradiction at its heart. Every time an “aspirational” policy is supported with taxpayer money – tax breaks for home ownership or investment properties, the tax deductibility of private school donations, public funding for private schools, tax breaks for the superannuation of the rich – those dollars cannot go elsewhere. The genuinely poor must continue living in poverty. Public school students must wait a decade for decent funding. Houses remain unaffordable to those without rich parents. Not holding anyone back and not leaving anyone behind are worthy sentiments. But leaving society largely as it is means the second of those sentiments is treated as less important than the first.

This is an edited extract of Sean Kelly’s Quarterly Essay, The Good Fight: What does Labor stand for? published Monday November 17

Sean Kelly will be discussing his essay with Peter Hartcher at Red Mill, Rozelle, Sydney, on Thursday, November 20, 7pm.

Read the full article here