For the first time in more than 50 years, humans are on the verge of returning to the moon. The Artemis II mission is preparing to launch as soon as March 6 to bring four astronauts in a loop around the moon, marking the closest anyone has been to our natural satellite since the Apollo 17 astronauts returned to Earth in 1972.

“For so long we’ve heard, ‘We’re going back to the moon,’” says planetary scientist Marie Henderson at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. Now, this generation of lunar scientists gets to be part of the action.

Originally, NASA was aiming to launch Artemis II as early as February 6. But after a “wet” dress rehearsal on February 2 identified a leak in the system for filling the rocket’s tanks with liquid hydrogen propellant, NASA decided to push the launch back to March to allow time for more tests and another dress rehearsal.

Artemis II won’t actually land on the moon. That’s a task for future Artemis missions, the details of which are still being hammered out.

That means this mission is more analogous to 1968’s Apollo 8, which was the first time humans orbited the moon. Like Apollo 8, Artemis II is above all a tech demo, aimed at testing the systems needed to keep humans alive in deep space and eventually land them on the moon. Science still plays a role.

“The primary focus [for Apollo 8] was getting to the moon and orbiting before the Russians,” says space historian Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo collection at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Artemis II is similar. “Although there is science here, a big focus of the program is testing out the systems to make sure that they’re ready for future exploration.”

But science is woven into Artemis II in ways Apollo 8 couldn’t even dream of, from the tech astronauts can use to the astronauts’ scientific training to the very architecture of the control room. This time, Henderson says, “science and exploration go hand-in-hand; we can’t do one without the other.”

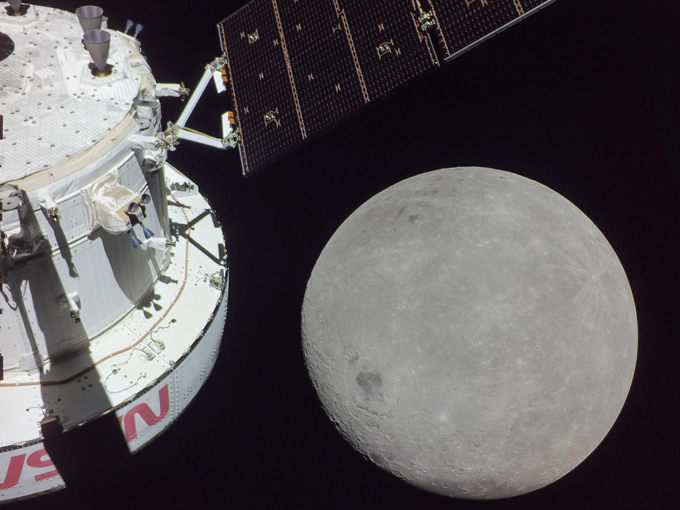

Artemis II will be the first time humans fly in NASA’s Orion space capsule, which circled the moon with manikins aboard in 2022 as part of Artemis I. The four astronauts — Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch from NASA, and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen — will launch on NASA’s Space Launch System rocket. Once in orbit, the Orion capsule will separate from its engines, orbit Earth twice to make sure everything works as expected, then fire its rockets to push the spacecraft onto a figure-8 lunar trajectory. The whole trip is expected to take 10 days and could go about 400,000 kilometers from Earth — farther than any humans have been before.

The overall goal of the Artemis program is to set the groundwork for a long-term human presence on the moon, and ultimately to prepare for human missions to Mars.

To that end, a lot of the science being done on the mission will use the astronauts as subjects. The astronauts will wear wristbands to continuously monitor their movement, sleep and stress levels. They will carry radiation sensors in their pockets to gather data on how many potentially harmful high-energy particles they are exposed to when they’re not protected by Earth’s magnetic field.

The astronauts will collect saliva samples in little stamp booklets to track changes in immune biomarkers before, during and after the flight. And the flight will carry small chips that look like USB thumb drives that contain cells developed from the astronauts’ own blood. This “organ-on-a-chip” is meant to mimic the astronauts’ bone marrow, which creates immune cells that keep astronauts healthy in space. Researchers back on Earth will study how genes within the cells changed as a result of spaceflight.

The moon itself is also a star of the mission. Artemis II could be the first time human eyes set sight on the farside of the moon.

Human eyes have seen pictures of the lunar farside, like those taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been orbiting the moon since 2009. The Chinese Chang’e-6 mission brought the first samples back from the farside in 2024. Artemis I snuck a peek at the farside too.

With all that robotic data, one might think there’s not much left for humans to add. But human eyes can pick up nuances that cameras can’t, Henderson says. The Artemis crew may notice quick changes, like the flash of a meteorite making a new crater. The astronauts will be able to look at the same spot from different angles and in different lighting conditions over the course of the flyby, giving a sense of depth and 3-D space that would take cameras months to create. And humans have different sensitivity to colors than cameras do. Henderson notes that the Apollo 17 astronauts spotted orange soil from orbit, which helped them choose a landing site. Samples of that soil were later determined to be bits of volcanic rock that erupted 3.6 billion years ago.

But unlike Apollo 8, which orbited the moon 10 times before returning to Earth, the Artemis II astronauts will have only a few frantic hours to observe the moon closely on their single loop.

Luckily, the astronauts themselves have had more science training than Apollo 8’s. Most of the early Apollo missions included all fighter pilots. The Apollo 8 crew studied up on lunar geology as much as they could. But the mission was planned quickly, and they had many other things to do.

“Apollo 8 was a highly technical and operationally difficult mission with a very tight schedule for science mission planning,” wrote NASA Manned Space Science director Richard Allenby in a report in 1969 on Apollo 8’s photography and visual observations. “That a worthwhile scientific plan was generated is a tribute to the scientists associated with the mission.”

Later Apollo missions, especially the final three, included more deliberate planning for science. “A lot of the science objectives evolved in the mid-1960s,” Muir-Harmony says. Starting with Apollo 15, “you have astronauts getting pretty incredible training in geology,” she says. “A lot of that important science was happening in those later Apollo missions, after some of the engineering objectives were already met.”

The Artemis II astronauts have been preparing for both engineering tests and science observations. The crew has had classroom training, regular “moon homework” and field expeditions to places on Earth that resemble lunar terrain, such as Iceland and Arizona. The crew and the science team have also run several practice simulations in which the crew looked out the window of a stand-in Orion capsule at a stand-in lunar map, which was sometimes a huge, inflated moon hanging from a crane.

These exercises are designed to help the crew make sure their descriptions of the scenery are scientifically useful. They’ll describe things like color, shape of features, textures and whatever else they notice. In a practice simulation, one of the crew described a feature as looking like a kiss, Henderson says.

“Our astronauts are scientists themselves,” Henderson says. In addition to their geology training, Hansen has a master’s degree in physics, and Koch did remote scientific field work in the Arctic and Antarctic before becoming an astronaut. “We think of them as an extension of our science team,” Henderson says. “I think that will increase the science return. Instead of little pieces here and there that we can extract, we know we’ll have a huge bundle of science we can dive into.”

Henderson is the Deputy Lunar Science Lead for Artemis II, a job that didn’t even exist during Apollo 8. During Orion’s lunar flyby, she will be leading a team of geologists and lunar scientists in the newly constructed Science Evaluation Room at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Her team will analyze data, ask questions and send guidance to the crew in real time.

The scientists will communicate with the crew via NASA’s Kelsey Young, who holds another new job: Science Officer. Young will be in the mission control room talking directly to the astronauts, along with other supporting officers who keep track of things like spacecraft health and communications. Her job is to make sure science is one of the factors considered when making decisions about what the astronauts will do and how the spacecraft will move — for instance, if the capsule should rotate to get a better view of the moon from the windows.

Henderson and her team will create a custom observing plan — an interactive map with annotated lists of things to observe, images of what the astronauts might see and note-taking spots to make drawings and annotations — and upload it to the crew’s tablets after launch.

The science team won’t know which lunar features the crew will be able to see until two days after launch, because the moon will be in a different position relative to the spacecraft depending on when Orion starts on its way to the moon from Earth orbit. But Henderson isn’t bothered by the uncertainty.

“There are so many different areas where I would be ecstatic,” she says. “I really don’t care when it launches, because I know it’s going to be good.”

Read the full article here