Despite being told from her late teens to look for lumps when it comes to spotting signs of breast cancer, Michelle McMahon— who was later diagnosed with a lesser-known but rising form of the disease—never felt one.

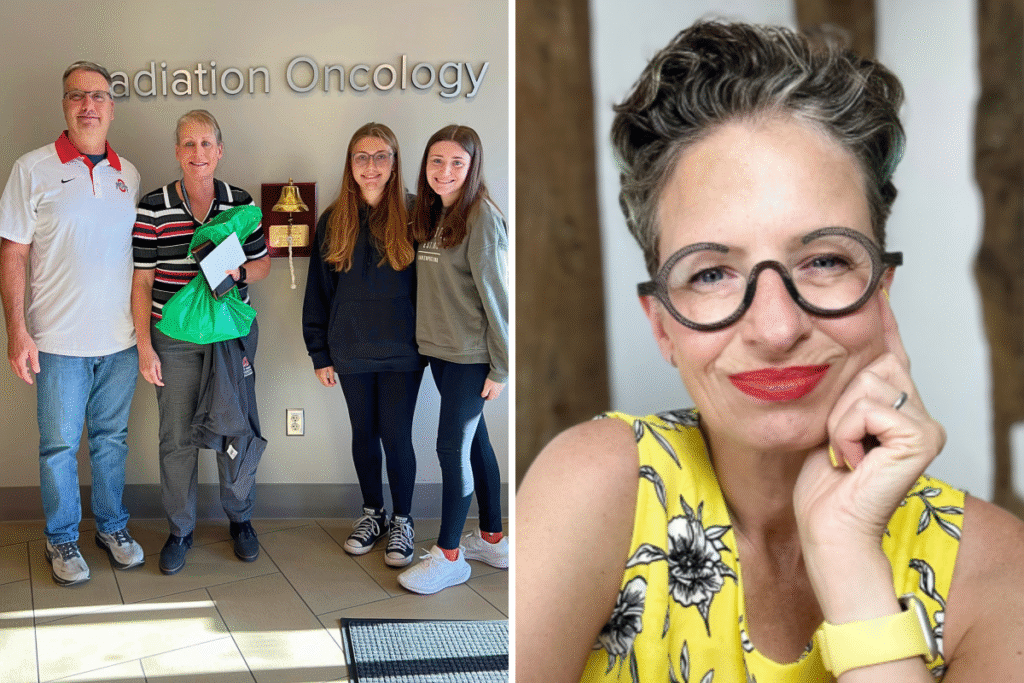

At 56, the Ohio-based finance operations manager had worked for years at The James Cancer Hospital’s department of radiation oncology, but she was still blindsided when she was diagnosed with lobular breast cancer—an elusive, understudied subtype often missed by routine mammograms and physical exams.

“There was no specific lump or tumor as the lobular cancer had turned the breast tissue itself into cancer,” McMahon—who lives with her husband, the youngest of her two daughters and the family’s Labrador—told Newsweek.

“Physicians have been telling me for years I have dense breasts—but more needs to be done to explain what that means and how women can advocate for themselves for better testing.”

An estimated 33,600 women in the U.S. are expected to be diagnosed with lobular breast cancer in 2025, according to new projections by the American Cancer Society (ACS).

Lobular breast cancer is the second most common form of breast cancer, but remains far less recognized than its counterpart, ductal carcinoma. October marks Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and experts say now is the time to raise public attention for a disease that is difficult to detect, underrepresented in research and often either misdiagnosed or found late.

The Surge in Lobular Breast Cancer

Unlike ductal cancer, which tends to grow in defined clumps, lobular breast cancer spreads in a single-file pattern, often leaving no noticeable mass for women told since their teens that the best way to spot breast cancer is by looking for lumps.

“Ductal cancers tend to grow in clumps, and they form lumps that you can see on a mammogram and that you can feel,” Dr. Liz O’Riordan—a breast cancer surgeon in the U.K. who was diagnosed with both ductal and lobular cancer in her 40s—told Newsweek. “But what lobular cancers do is they lack a protein called e-cadherin…Without it, the cells grow in sheets.”

This growth pattern makes the cancer harder to detect on imaging and easier to spread to surrounding areas.

“There may be just some diffuse thickening… and they don’t form lumps that you can feel,” she added. “They’re not always seen on a mammogram.”

Dr. Aria Mariam Roy, a breast cancer specialist at the Ohio State Comprehensive Cancer Center who treated McMahon, said increasing diagnosis rates may be partly due to better recognition by pathologists and the use of more advanced imaging tools.

She also anticipates artificial intelligence being applied more frequently in future practices to help speed up diagnoses.

“Previously, we were calling a lot of lobular breast cancer patients as mixed type or mixed ductal and lobular,” Roy told Newsweek. “But now, we know that lobular breast cancer is actually a different one.

“It may have been there before but now we are using techniques like MRI scans for detection and can finally recognize it.”

One Patient’s Journey

McMahon’s journey began in October 2023 when a routine mammogram showed calcifications. Thinking them quite harmless, she did not follow up until February 2024.

“I didn’t think it was a big deal,” she said.

But further testing, including a mammogram, sonogram, CT, stereotactic biopsies and MRI confirmed what a stunned physician told her mid-sonogram: “Oh yeah that’s cancer—see how it radiates out like the sun?”

“I cried and then went into denial,” McMahon said. “After all, in the movies, they call you into an office and give you the bad news. They don’t just blurt it out, right?”

McMahon had no choice but to face her heartbreak and fear— and swiftly underwent a single mastectomy, four rounds of chemotherapy, a month of daily radiation, reconstruction surgery, She is currently on the cancer drug Kisqali and hormone therapy. She credits her care team at Ohio State University (OSU) for helping her manage the mental and physical burden of treatment and get back to life.

“I got to watch my eldest daughter graduate in 2024 and go on to college,” she said.

‘Sneaky’ and Understudied

Lobular cancer’s unique pathology also means that it responds differently to treatment.

O’Riordan’s own experience underscored this fact; when chemotherapy eliminated her ductal tumor entirely there were still 13 centimeters of lobular cancer left when doctors examined her tissue after a mastectomy.

“The chemotherapy hadn’t touched it, and it wasn’t seen on the mammogram or the MRI,” she said.

She later experienced two recurrences on her chest wall—both lobular. Like McMahon, O’Riordan is in her 50s and has been placed on lifelong hormonal therapy.

“We now know that lobular cancers aren’t very responsive to chemotherapy,” O’Riordan said. “They are very hormone sensitive, but there’s not a lot of data to show that.”

This lack of data is partly because most breast cancer trials have not historically distinguished between lobular and ductal subtypes, as Roy explained.

“It was all done by receptor type—ER positive, HER2 positive, triple negative,” O’Riordan added. “So, we don’t have that data to say how many were lobular or ductal and examine if there was a difference in the way they responded to various drugs.”

She and Roy agree that the classification gap needs urgent correction.

“We need to start putting money in to see: if they’re not responding to chemotherapy, what do they respond to?” O’Riordan said.

Spotting Lobular Breast Cancer

Lobular breast cancer is also linked with dense breast tissue—a common feature among younger, premenopausal women.

“If the patients have dense breasts…You need to talk to the provider about that,” Roy said. In those cases, she recommends supplementing mammograms with ultrasounds or MRIs.

Roy also draws attention to a newer diagnostic tool: the FES PET scan, which is useful for identifying estrogen-driven cancers.

“Lobular is highly hormone positive,” she said. “…and this scan helped me to identify lobular cancer in cases where CT scans were negative.”

With the lengthy path to diagnosis already a challenge, Roy and O’Riordan emphasize that the symptoms themselves can be hard to spot. They highlight the importance of self-exams, particularly because mammograms can miss lobular cancers.

“We know that over half of all women don’t check their breasts regularly,” O’Riordan said. “And the earlier you pick up a change, the less treatment you’re likely to need.”

How To Check Your Breasts Correctly

O’Riordan wants women to keep several things in mind when it comes to self-examining their breasts.

- You need to be looking at your breasts, not just feeling, because looking in the mirror can often be the first way you spot a change.

- This can be a change in the size or shape of the breast.

- Look for swelling, rashes, visible lumps or if the nipple has been pulled in.

- Put your hands on your head and your hands on your hip to stretch out the breast tissue. If there is cancer, it can stop the skin stretching and moving, so you might see a dimple. This effect can be common with lobular cancer.

- When feeling, look for hard and “knobly” lumps that stand out from the rest of the breast tissue or any area that feels thickened or different to the other side.

- Keep an eye out for bloody or watery nipple discharge and armpit lumps.

“If you spot any change and it’s still there after one or two weeks, then you should see your doctor and ask to be referred to a breast clinic, just to be on the safe side,” O’Riordan said. “Most people won’t have breast cancer, but doctors need to see you to make sure you don’t.”

She added that women need to be self-examining once a month, preferably in the middle of their menstrual cycle if they are still having periods—as that is when their breasts will be “less lumpy.”

The Push for Greater Awareness

McMahon believes that awareness and early intervention were key to her survival.

“Had the calcifications not been caught in October, by March…I’d have definitely been going to the doctor with issues surrounding the physical changes in the breast,” she said. “Research needs to be done to help find ways to discover this disease sooner than stage 2 or 3.”

(Lobular breast cancer is classified as stage 2 when it is at least three-quarters of an inch across and has spread to nearby lymph nodes, or if it is two inches or across but hasn’t spread. In stage 3, cancer spreads to a greater number of lymph nodes.)

Both Roy and O’Riordan point out that lobular cancers can recur in unusual places—including the stomach, bladder or even gynecological organs—further complicating monitoring and follow-up care. O’Riordan explained that this is because lobular cancer, with its sheet-like cell growth, can blanket and wrap around the lining of organs.

“Patients may not know that,” O’Riordan said. “We need to raise awareness and we need to know when to call a doctor if we’re worried.”

For now, McMahon remains on medication and is preparing for a second revision of her reconstruction surgery in January.

“I’m doing well and feeling very grateful,” she said.

O’Riordan is also okay. Both women class themselves as among the lucky ones who were able to be treated before things went too far.

“I’ve just had my monthly treatment that stops me producing estrogen,” O’Riordan said. She added: “Touch wood, I’m cancer free and everything’s good.”

O’Riordan, who wrote The Complete Guide to Breast Cancer and Under the Knife, wants women to feel comfortable advocating for themselves when face-to-face with their doctor.

“Often patients are having to fight to say, I need an MRI as well as a mammogram,” she said, “and I think having general guidelines to say lobular cancers are sneaky will do plenty of good.”

Is there a health issue that’s worrying you? Let us know via health@newsweek.com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured on Newsweek.

Read the full article here