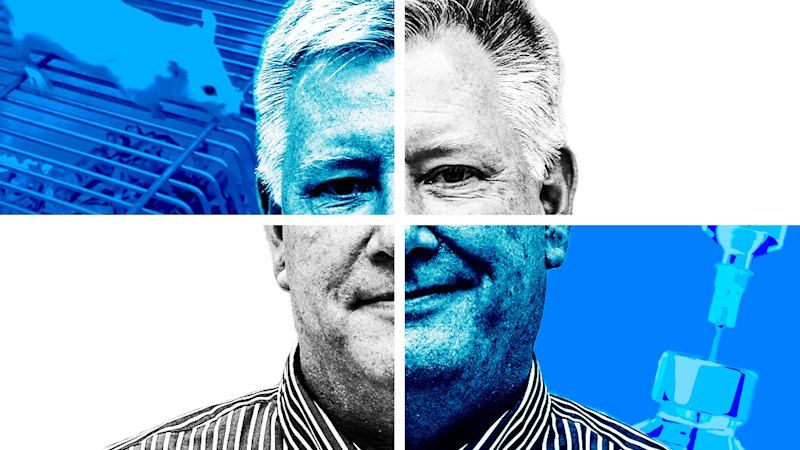

A human trial of a cancer drug based on research done by accused Australian scientific fraudster Mark Smyth has collapsed, confirming the fears of Smyth’s collaborators that the drug did not work.

The cancellation of the trial is likely to have cost sponsor GSK tens of millions of dollars, as well as wasting the time of participants with cancer.

Smyth was once one of Australia’s top cancer researchers, winning international awards, receiving tens millions of dollars in taxpayer grants, and coming to be viewed as “godlike” by colleagues while he worked at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and, later, the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute.

His glittering career came to an abrupt halt in 2021 when this masthead revealed he had been accused of research misconduct by QIMR and referred to state corruption authorities.

Smyth’s work on a cell receptor called CD96 laid the foundation for British pharmaceutical giant GSK to develop a drug called nelistotug, designed to harness the immune system to melt cancer.

Despite Smyth’s career coming unstuck in 2021, the company pushed ahead with nelistotug, launching a trial in 316 volunteers with head and neck cancers in Europe and America in 2023.

This masthead can now reveal that trial, due to run to 2027, has been cancelled due to unpromising early results.

“The program was terminated based on the interim analysis of the GALAXIES H&N-202 phase II trial, which did not show a clinically meaningful improvement in the primary endpoint of objective response rate,” a GSK spokeswoman said.

One of Smyth’s former colleagues who worked directly with him on the CD96 research said they were sad for the volunteers but not surprised the drug had failed.

They had been unable to replicate Smyth’s promising results in the lab.

“I feel really bad for the patients that they were given false hope in the first place,” the former colleague said. “They could have been enrolled in another clinical trial testing something that might have actually worked,” they said.

“It has been a waste of money to organise the clinical trial, and it has also given false hope for people. I think it should be a warning sign if all the positive results have been generated by just one research group.”

Smyth has never publicly commented on the allegations he faces and could not be reached for comment.

The race to commercialise CD96 comes to a messy end

CD96 is a receptor on the surface of many immune cells.

It binds, like a lock in a key, to a protein on some cancerous cells called CD155.

In 2014 Smyth was senior author on a paper in the prestigious journal Nature Immunology that suggested that binding may deactivate the immune response, allowing tumours to grow unchecked. While other papers Smyth co-authored have been retracted, the Nature Immunology paper has not.

By blocking CD96 from binding to CD155, the tumour would theoretically be opened to attack by the immune system.

This type of treatment is known as immune checkpoint therapy; blocking other receptors like PD-1 has proved an extraordinarily successful way of harnessing the immune system to fight cancer.

Smyth hoped CD96 would be another success. We are “at the dawn of a new opportunity in terms of therapy”, he told Nine, owner of this masthead, in 2014.

In 2020, GSK filed a patent for an antibody that binds to CD96. “The first paper indicating CD96 as a potential immuno oncology target was published by the lab of Professor Mark Smyth in 2014,” the patent reads.

GSK also paid US$625 million to another company for the rights to co-develop another drug targeting CD155 in 2021, while competitor Bristol Myers Squibb paid US$200 million in 2021 for the rights to collaborate on a CD96 antibody.

But by early 2025, things were going pear-shaped. GSK dropped its other CD155 drug, taking a US$629 million impairment charge. Then in late October it dropped the CD96 research. BMS walked away from its US$200m deal in 2024.

It is not clear how much GSK spent developing nelistotug. The drug reached phase 2 trials; a new drug typically costs about US$173 million to develop, with the vast majority of that spending for clinical trials.

Even when there are no questions about research integrity, about 75 per cent of drugs fail phase 2 studies.

Professor David Vaux, the former deputy director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research who did much of the work exposing Smyth, said QIMR had a responsibility to warn drug companies building off Smyth’s research about the allegations of research misconduct.

“Patients involved in clinical trials must give consent, and that consent must be informed, and that would include information that concerns about the preclinical data underpinning the trial were being investigated,” he said.

A spokeswoman for QIMR did not answer questions about whether it directly warned GSK about Smyth’s research.

“GSK’s CD96 program is completely separate to the CD96 program based on Professor Mark Smyth’s work, and as such we cannot comment on this,” she said.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

From our partners

Read the full article here