Crush

James Riordon

The MIT Press, $40.25

Isaac Newton confessed that he had no idea what gravity was. The 17th century English polymath knew what it did, and he described it with a universal law of gravitation. But where the law came from, and why everything seemed to obey it, Newton could not say. More than 300 years later, ŌĆ£gravity remains both the most familiar and most mysterious of all the forces,ŌĆØ author James Riordan writes in Crush.

That strange dichotomy opens the bookŌĆÖs wide-ranging exploration of this fundamental force of nature. RiordanŌĆÖs moves through biology, physics and history with enthusiasm and nerdy humor, which helps carry readers through ideas that grow steadily denser.

Gravity is so interwoven with daily life that it exists quietly in the background. Humans notice it mainly when it shifts, such as in an elevator lurch. But it literally shapes life on Earth, Riordan explains. For instance, it determines where the heart sits in a snakeŌĆÖs body. It also limits how massive animals can become. In outer space, the weightlessness of microgravity reshapes astronautsŌĆÖ bodies: The torso swells, senses dull, and bones and muscles slowly degrade.

Beyond the solar system, gravity may determine which planets can host life at all. Riordan shows how a planetŌĆÖs mass governs whether it can retain an atmosphere and sustain liquid water. He then looks beyond traditional habitable zones to rogue planets drifting through space with no star to warm them. On these worlds, gravity traps heat from planetary formation and radioactive decay beneath thick ice shells, potentially sustaining subsurface oceans for billions of years.┬ĀBecause such rogue planets vastly outnumber planets with stars, Riordan suggests they could statistically be among the most likely places for life to exist in the universe.

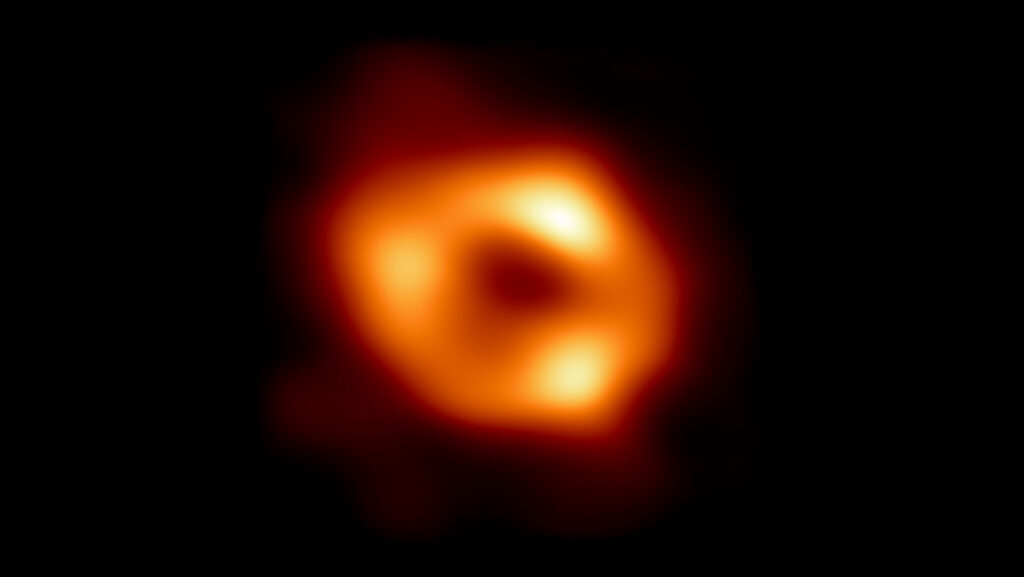

Explaining physics is where Riordan shines brightest, providing a genuine conceptual footing via an arsenal of metaphors. Take black holes, regions of spacetime where gravity is so powerful that not even light can escape their grasp. The anomalies can be understood using nothing more exotic than a running kitchen sink. ŌĆ£I have a black hole in my kitchen,ŌĆØ Riordan announces, before walking readers through squishy spacetime. He connects abstract frameworks to everyday technologies, including GPS and cell phones, and to unexpected uses, such as probing the pyramids of Giza.

Riordan is careful to emphasize just how much about gravity remains unknown. Our understanding runs from NewtonŌĆÖs law to EinsteinŌĆÖs theory of gravity, general relativity. Beyond that, the ground becomes less firm. Efforts to unify gravity, which explains stars and planets, with quantum mechanics, which governs protons and electrons, are still in progress. And at the same time, about 95 percent of the universeŌĆödark matter and dark energyŌĆöremains unexplained.

CrushŌĆÖs scope and uneven structure can make the story feel fragmented even as the ideas remain compelling Vivid thought experiments, such as listing the ways one could due inside a black hole and calculating the size and structure of a theoretical giantŌĆÖs bones, carry much of the weight. Still, the book succeeds in what it sets out to do: make gravity feel both familiar and strange.

Readers may not find a single, tidy story, but they will come away newly alert to a force that is everywhere and shapes everything.

Buy┬ĀCrush┬Āfrom Bookshop.org.┬ĀScience News┬Āis a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.┬Ā

Read the full article here