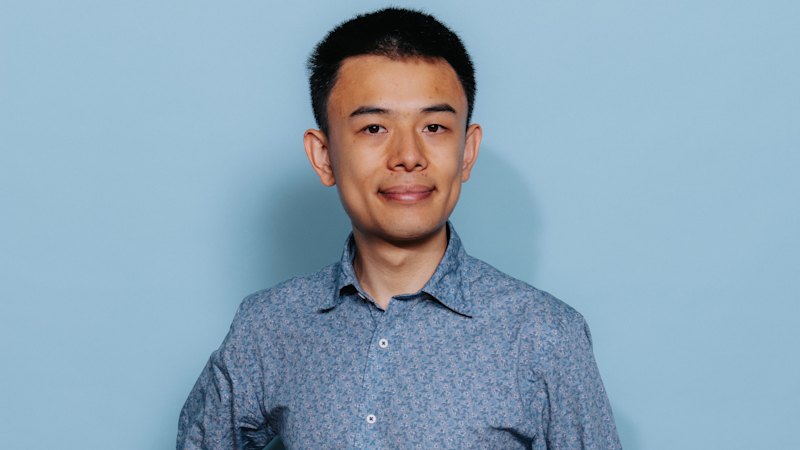

Yao Xiao from St Aloysius’ College topped the state in English extension 2 in the 2025 HSC.Credit: James Brickwood

The leftovers: Aesthetic autonomy in Shakespeare’s oeuvre

An empty stage.

HAMLET walks on stage and stands in the centre.

The CRITIC sits in the empty theatre, peering at the wings.

Leftovers. The scraps left behind after any unfinished meal. For some, disposable; for others, a boon!

Type ‘leftover’ into Google, and you will be treated to an array of recipes for meals made with leftover roast lamb, mashed potatoes or barbeque chicken — enough to make the Falstaff within each of us salivate.

Nonetheless, after a meal, they linger at the edge of the plate.

And just as these leftovers linger, waiting to be thrown into a wastebin or refrigerated to be savoured anew, there are characters in literary texts who, too, linger in the peripheries of print and the edges of the stage, undigested into a coherent narrative whole — characters whose arcs seem unresolved. Their authors, seemingly, do not quite know what to do with these creations.

Think of Antonio in William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, who remains unpartnered in the play’s final scene, and whose primary role is — paradoxically, in a comedy — to be the “sad one”. Or his namesake, Antonio, in Twelfth Night, who is likewise excluded from comic revelry, denied the fulfilment of marriage. Or yet another Shakespearean Antonio, of The Tempest, who speaks only two lines in the final scene and remains silent as his brother, Prospero, offers forgiveness, dampening the possibility of reciprocal, Agape love promised by Prospero’s olive branch.

I term such figures ‘leftover characters’. If, as literary critic Jonathan Culler argues, “[c]haracter is the major aspect of [literature] to which structuralism has paid least attention”, these ‘leftover characters’ have been especially starved of critical attention.

To redress Culler’s critique, literary theorist Alex Woloch proposes a model he terms ‘character-space’: the relationship between “an individual human personality and a determined space…within the narrative”. In any palatable dish, or work of coherent narrative art, there is the ‘hero ingredient’ — what Woloch denotes as the “central condition of the protagonist”, who serves as the text’s “referential core”. This ‘referential core’, I argue, is ‘genre’ by another name, congruent with John Frow’s definition of genre as “a set of highly organised constraints on…the interpretation of meaning”. A text’s ostensible genre is often aligned with the protagonist’s ‘central condition’: Hamlet reads as tragedy because Hamlet is a tragic figure, just as Viola and Sebastian’s comic trajectories render Twelfth Night a comedy.

Thus, generic categories emerge not as properties of texts per se, but rather as emergent effects of how characters are positioned, privileged and resolved within dramatic structures.

Leftover characters, I posit, are those excluded from the particular generic conventions that govern their protagonists: characters whose presence challenges both the semantic meanings and syntactic patterns that would otherwise provide narrative closure.

I will treat these offcuts, these surplus ingredients, these leftover characters as boons.

——————————————————

Not Even Food for Worms: Horatio in Hamlet

HAMLET

[Stops pacing, considers] Horatio…Now there be a perfect ‘leftover’: supportive, but never centre stage. “Yes, my lord.” “Indeed, my lord.” An attendant lord if ever there was. He speaks but barely three hundred lines! And I a thousand and hundreds more!

CRITIC

In modern parlance, we would diagnose you with main character syndrome.

Why does Horatio live?

He expresses suicidal ideation: his best friend had just died, and the Danish Royal family had been annihilated. In Shakespeare’s Elizabethan milieu, with its faith in the Divine Right of Kings, dynastic collapse represented cosmic catastrophe. He is akin to the lone survivor of an apocalypse, ostensibly marking him immediately as a leftover character.

Yet, his survival, simultaneously, seems demonstrably teleological.

His duty is outlined clearly by Hamlet: to “tell [Hamlet’s] story”.

In tragedies, there are always characters who survive the catastrophe to catalyse future regeneration; I label them ‘tragic historians’. As critic Andrew Hui notes: [Their] concluding speeches underscore…that [these characters] need time to think about the actions that have just occurred.

Tragic historians serve two distinct functions within tragedy’s syntax. Some exist to make sense of what A.C. Bradley calls “tragic mystery” – figures who attempt to impose narrative coherence on chaotic events, such as Ludavico at the end of Othello. Others function as moralisers who can swiftly alchemise the tragedy into didactic instruction, like Edgar in King Lear, urging onlookers to “speak what we feel”.

‘There is something especially strange about Hamlet: only Horatio survives as witness to the tragedy.’

Both archetypes satisfy tragedy’s telos: discerning meaning from suffering. The denouement provides the interpretive framework that processes catastrophic events as cathartic and meaningful: products of inescapable fate or avoidable human error. Tragedies are causal, not entropic. And while Shakespeare’s tragedies seemingly disrupt Ancient Greek tragic obsessions with moirai, they do fulfil Aristotle’s ideal for tragedy to have “an air of design” — what Bradley extrapolates as the “tragic fact”, where “the calamities of tragedy…proceed mainly from actions”. Indeed, I argue, Shakespearean tragedy is entwined with Christian theology, in the same way comedy is entangled with Christian marriage dogma, as tragic historians and moralisers function like the Four Evangelists: figures who inscribe a redemptive arc to suffering. As [critic Northrop] Frye argues, “suffering” in Shakespearean tragedy “has something subdivine about it”, especially in light of Christian perceptions with “tragedy as an episode in…the larger scheme of redemption and resurrection”. Despite the bitterness of tragedy, there is always a sweet aftertaste.

Loading

So that’s it. Horatio isn’t a leftover character! Tragic historians clearly are a generic feature of tragedy.

Well, not quite. There is something especially strange about Hamlet: only Horatio survives as witness to the tragedy. This anomaly concentrates the entire burden of historical transmission onto a single figure, one who paradoxically abandons the historian’s interpretive duty, removing him from the generic structure of tragedy entirely. Horatio eponymises historical consciousness, but a consciousness stripped of its redemptive capacity.

He is a leftover character after all.

——————————————————

Postscript

In our own era of resurgent authoritarianism and ideological polarisation, totalising discourses seek to enlist cultural works as soldiers in ideological warfare: from right-wing Australian politician Craig Kelly conscripting George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four as a screed against COVID lockdowns, to British Conservative Party MP Nadhim Zahawi claiming Shakespeare as “a natural Tory”. For every reimagination of a canonical text as a “woke panto”, as theatre critic Andrzej Lukowski described the recent musical & Juliet, or reclamation of Shakespeare as a ‘proto-feminist’, there is an insidious social media account smuggling white supremacism into nostalgia for classical European aesthetics.

[Scholar Harold] Bloom’s anxieties about the “School of Resentment” threatening to “overthrow the Canon”, whilst sometimes sounding like the rants of a conservative curmudgeon, do gesture toward a genuine concern: that ideological readings risk reducing Shakespeare’s complexity to predetermined political categories. Yet we need not choose between Bloom’s Bardolatrous aestheticism and the reductive instrumentalism he opposes. Instead, leftover characters reveal a third way: we can rehabilitate the canon, not by superimposing anachronistic feminist, or Marxist readings onto Shakespeare’s plays, but by recognising the contradictions intrinsic to the works. [Twelfth Night’s] Antonio and [Hamlet’s] Horatio’s undigested presence in their respective plays point to the limits of religious orthodoxy without endorsing or condemning religiosity; they destabilise the sanctity of the pieties that seek to control moral reality and enshrine social order.

Leftover characters may seem superfluous, but as Voltaire declared, “the superfluous [is] a very necessary thing”. A text bereft of its protagonist is not simply a collection of measly side dishes and unfulfilling amuse-bouches. Rather, stripped of its ‘referential core’, like a cleft apple, a text is still full of sound and fury — not signifying nothing, but evoking everything ideological systems suppress. In preserving these remainders, these morsels, Shakespeare delivers what our own historical moment desperately requires: art that resists ideological conscription.

As Falstaff protests, “[i]f sack and sugar be a fault, then God help the wicked” — so let us savour these leftovers, recycle them, like the savvy home cook, rather than wastefully discarding them from dramaturgical and critical practice. And if these leftovers be the food of critical nourishment, give me excess of them.

Exit CRITIC

HAMLET remains centre stage, alone, looking out at the empty theater.

HAMLET

If there be no purpose for me, I shall shuffle off this theatric coil. I shall waste your time no longer. The rest is silence.

[He does not move.]

This is an edited extract of 2025 HSC English dux Yao Xiao’s extension 2 essay. Yao attended St Aloysius’ College.

Read the full article here