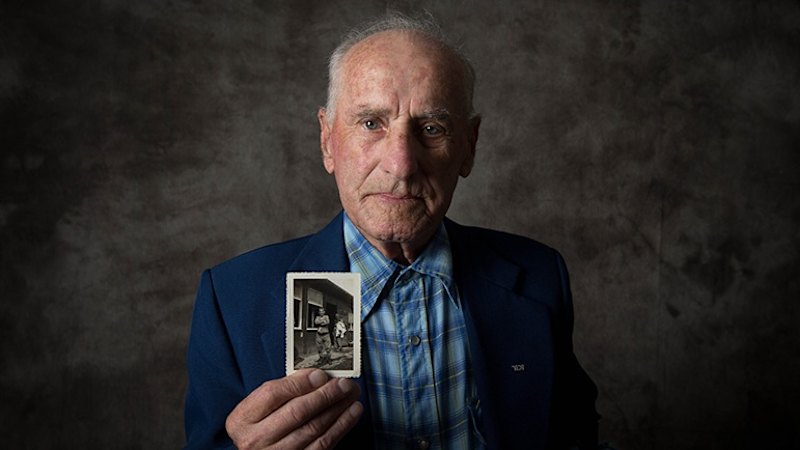

Jack and Nita Meister on their wedding day in the Maccabean Hall in 1951.Credit: Courtesy: Sydney Jewish Museum collection

A few months later, Jack asked her father for permission to marry. The reply: “If she likes you, and you make her happy, of course”. They were married in the Maccabean Hall in 1951.

When the Sydney Jewish Museum was established within the Maccabean Hall in 1992, Meister signed up to volunteer. By the time I met him, he had been coming in every Thursday for 24 years.

There is beautiful magic in the power of place. Within this building, Meister found safety, love and purpose over more than six decades.

But in all this time, he had stood quietly in the exhibition space, directing people or occasionally showing his tattoo B488 on his forearm from Auschwitz, a glimpse into his story. Most survivors volunteering at the museum spoke to large student groups. Why not him?

I plucked up the courage to ask. He couldn’t bear the thought of burdening innocent young people with the pain of his past.

What about adults?

Jack Meister recalled how in August 1942, the Kielce ghetto where his family was living was liquidated. Credit: Fairfax Media

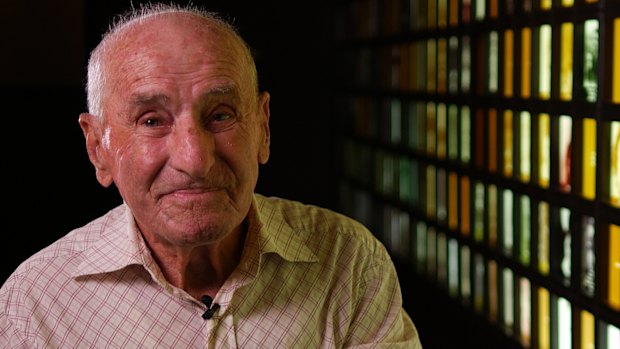

He laughed. A joy-filled, child-like laugh. The kind you hear for a genuinely good joke. “What do I have to say?”

This felt like an invitation for a nudge. A few weeks later, he agreed to speak to volunteers undertaking the guide course. They were patient, interested and encouraging. He spoke for nearly two hours.

Colossal friend: Jack Meister and Rebecca Kummerfeld at the Sydney Jewish Museum.

From that first tentative telling, Meister’s story connected with people. Soon he started speaking to adult groups. Then, cautiously, senior students. He worried about the kids. But after receiving letters from them describing the impact of his story, he agreed to speak to more student groups. And speak he did: every Thursday (and the first Tuesday of the month), to tens, then hundreds, then thousands of students.

When I left the museum, I grieved the loss of our regular conversations. I would phone him on Thursdays, grinning as he answered with his signature “Hey-looo?” – his accented greeting, beaming joy through the phone line. He’d tell me about the “tremendous” questions his students had asked that day.

In recent years, Meister told his story for TV, radio, news broadcasters and publications. He joined the Holocaust educational program March of the Living, spoke to dignitaries and presented at communal commemorations.

Meister was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for his service to the Jewish community of Sydney in 2023.

For those who heard him speak, there was a word he would frequently use to describe his proudest moments: “colossal”. Moving to Australia, sharing his story for the first time, being awarded an OAM – these were all “colossal”. Indeed, Jack Meister himself was, and will always be, colossal; a man of great care, resilience, bravery and joy through the many chapters of his life. He died on November 16 and leaves a colossal hole in our community.

He is survived by his daughter Leanna, grandsons Mark and David, and great-grandchildren Iris, Isaac and Leon.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here