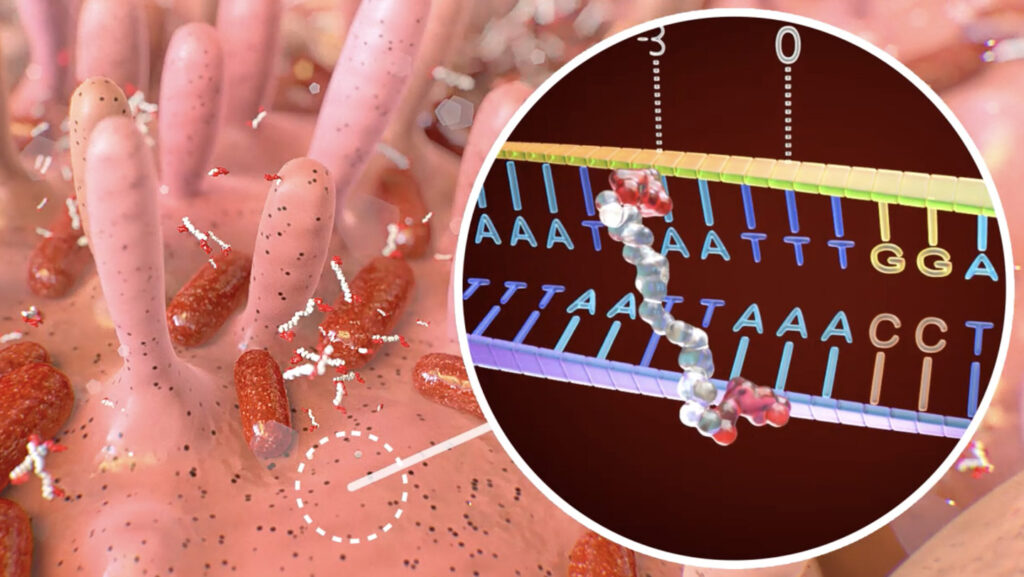

The microbial toxin colibactin has just the right shape to snuggle up to DNA — but its embrace is unfortunately more cancerous than cozy.

Colibactin is produced by bacteria in the gut and causes mutations implicated in colon cancer. It bears chemical motifs so good at damaging DNA that scientists call them “warheads.” And now, a close look at colibactin as it reacts with DNA has revealed how it seeks and destroys: Its structure grants it a pesky proclivity to target particular stretches of DNA, researchers report December 4 in Science.

The discovery forges a strong link between colibactin and specific “fingerprints” of mutation observed in colon cancer. Scientists could eventually use those fingerprints to develop tests for colibactin exposure and arm doctors with better tools for evaluating cancer risk.

Most gut bacteria are beneficial or neutral, but some, including some strains of Escherichia coli, produce toxins like colibactin and are downright destructive. Since colibactin was discovered in 2006, evidence that it contributes to colon cancer — a disease that will strike about 1 in 25 people in the United States in their lifetimes — has been piling up.

One of the strongest hints comes from the unique patterns of mutations carried by human colon cancers. Colibactin doesn’t damage DNA willy-nilly. It inflicts specific mutations within particular short “words,” or sequences, written in DNA’s four-letter chemical alphabet. Those mutations show up in the genetic fingerprint of 5 to 20 percent of colon cancers. E. coli carrying the genes required to build colibactin are found more often in colon cancer patients than in healthy people. And experiments have linked colibactin exposure to DNA damage and cellular aging in human cells and tumor formation in mice.

But despite all this promising evidence implicating colibactin in cancer, the molecule’s structure — an explanation for how it produces its signature mutations — proved elusive.

“Because it’s unstable, nobody was actually able to isolate it,” says chemist and biologist Orlando Schärer of the University of Pittsburgh, who wasn’t involved in the work and wrote a perspective piece in the same issue of Science. Free-floating colibactin broke down too quickly to characterize, so scientists had only ever studied fragments or more stable but imperfect analogs of the real molecule.

Chemist Emily Balskus and colleagues got around this problem using living gut microbes to produce the chemical. “This is very unconventional because chemists prefer to use individual, purified molecules,” says Balskus, of Harvard University. The team identified colibactin’s favorite short DNA sequences, then used them as bait to bind the microbe-made colibactin. Once some colibactin latched onto the DNA, the researchers determined the structure of the combo using techniques like mass spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. “What they did is really quite special,” Schärer says.

Bothering with the true, unstable form of the molecule paid off: It turned out that colibactin’s unstable core is key for determining the sequence it targets. That core contains a nitrogen-bearing group loaded with positively charged protons, which help the molecule recognize and stick to its preferred sequences. Attached to this core are two long arms decorated with additional sticky nitrogen groups and tipped with triangles made up of three carbons — the “warheads” that can attack and form chemical bonds to DNA.

This structure is a recipe for trouble, since it allows colibactin to slip in alongside a specific DNA sequence, grab hold of both strands of the double helix and bond to them. A chemical bridge between both strands of DNA — what’s called an interstrand cross-link — keeps DNA from unzipping to replicate or be read by the cell’s protein-making machinery. Cells can repair that damage, but the repair is often messy and leaves behind specific kinds of mutations. And colon cancers associated with colibactin often carry those mutations in precisely the DNA sequences Balskus and her colleagues showed are targeted by colibactin’s structure.

“This is the closest we have come to solving [colibactin’s] structure, a journey that has taken the field almost 20 years,” Balskus says. “As a chemist, I find this very exciting!”

Read the full article here