Hungary’s top diplomat told Newsweek that the only path to obtaining peace in Ukraine and ensuring Europe’s security ran through a stable relationship between the United States and Russia, vowing Budapest would not back down in the face of pressure from EU and NATO allies on this front and others.

Speaking Tuesday on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York, where his counterparts from Washington and Moscow were soon set to meet, Hungarian Foreign Affairs and Trade Minister Peter Szijjarto said his country would “welcome such an event, because we in Central Europe have a very clear historical experience.”

“And this experience says that in case the Americans and the Russians are able to maintain a civilized cooperation, then we in Central Europe enjoy a better security,” Szijjarto told Newsweek. “If the Americans and the Russians fail to maintain a civilized relationship, then we are concerned about the consequences on our security.”

But as President Donald Trump suddenly took aim at Russia in a remarkable shift Tuesday — promised ongoing U.S. military aid to NATO’s pro-Ukraine war effort and even suggesting Ukraine could take back territory it has lost — Szijjarto maintained only a deal between the U.S. leader and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin could pave the path toward peace in Ukraine.

He argued such rapprochement, for which both Trump and Putin had previously called, could also make strides in stabilizing the region.

“I really do believe that the only solution for this war is a comprehensive American-Russian agreement,” Szijjarto said. “If there’s no Russian-American agreement, I see very limited hope for peace here. The Russians and Americans should come to a big agreement, part of which could end up in in peace returning to the central part of Europe, certainly.”

‘The Only Hope for Peace’

Yet many on the continent, including Poland, are calling for tougher measures toward the Kremlin and have expressed skepticism toward Trump’s diplomatic engagement with Russian President Vladimir Putin—with whom Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has also retained ties.

But if the White House’s overtures have failed to make sufficient progress, Szijjarto argues it may be Trump’s detractors who are to blame for adopting policies that have fueled the conflict rather than quell it.

“I have to tell you that we do consider President Trump as the only hope for peace in Ukraine,” Szijjarto said, “because during the time before him taking office, there had been no hope, because both the former American administration and the current European leaders are very much pro-war. They are more interested in prolonging the war than concluding it, and therefore it is only President Trump who can make the change here, who can give hope for a peaceful settlement.”

“So, I think that his efforts must be respected pretty much,” Szijjarto said. “And I can tell you that if European leaders had not put so many efforts in undermining the peace process, I would say he would have had a good chance to resolve the issue until now.”

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022, a number of European countries have taken aim at Hungary over its efforts to maintain a neutral position. Orban, who has served as premier since 2010 after previously leading from 1998-2002, declared early on that his nation would not join efforts to send weapons to Ukraine, nor would it participate in economic sanctions against Russia.

On top of this, Szijjarto said, “we have a big Hungarian community in Ukraine, the right of which have been very heavily violated by the Ukrainian state.”

For these positions, and particularly for Hungary’s push for ceasefire and negotiations as “the only solution” to the war, he said “we have been accused of being the puppet of Putin and the spies of Russians by those who are now [calling for] the same ceasefire talks.”

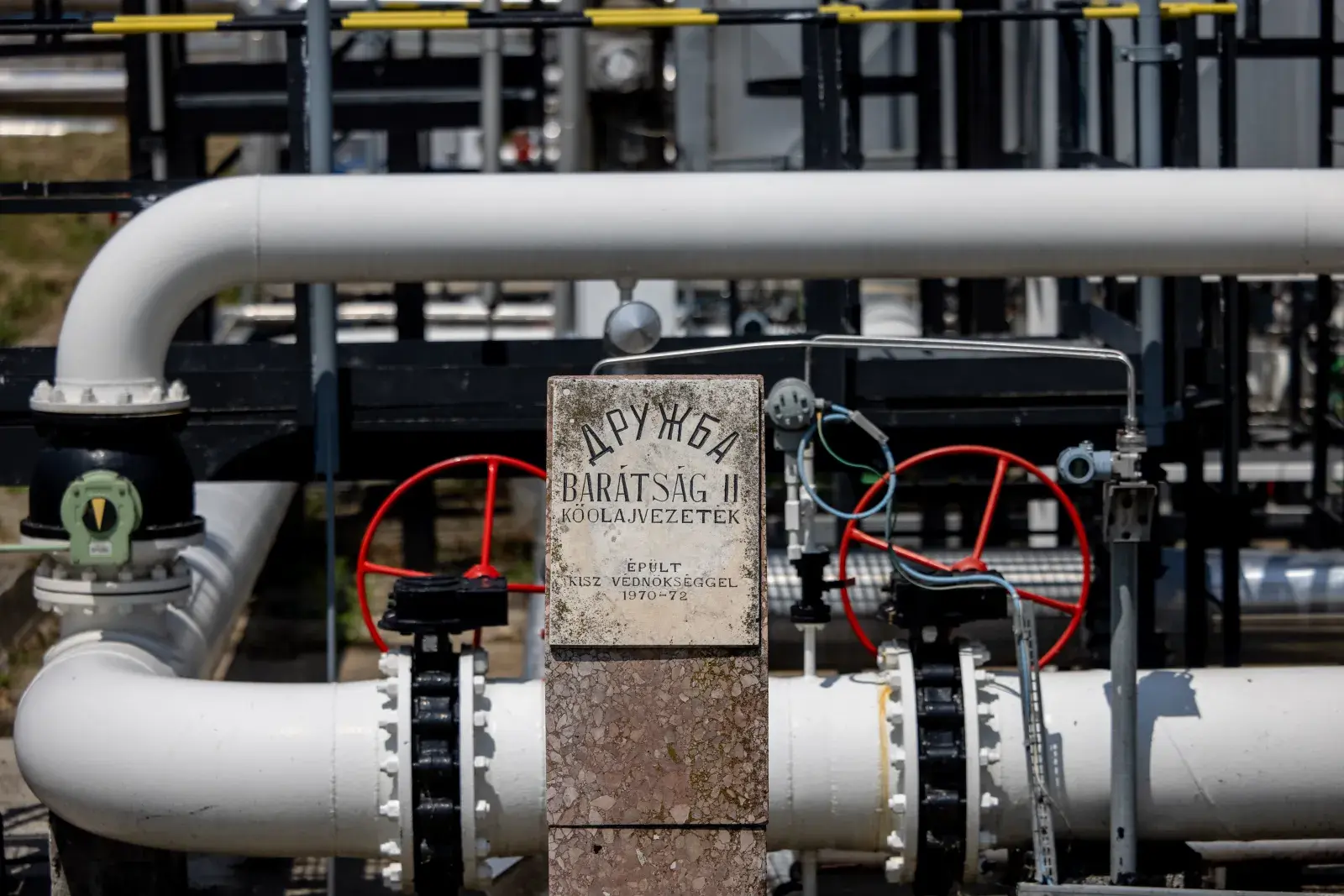

Crude Geography

The latest showdown has erupted over Russian oil and gas shipments, which Trump is calling on all EU countries to suspend. Hungary has steadfastly refused, even in the face of reported plans by the European Commission to unlock more than $465 million in frozen funds as members seek to win over Budapest’s vote to tighten restrictions against Moscow.

Szijjarto says Hungary’s position is not rooted in politics or ideology, but rather geography.

“Being a landlocked country with a certain infrastructure, the biggest part of the energy supply is determined,” Szijjarto said. “We have two oil pipelines leading to Hungary, one from Russia, the other one from the Adriatic Sea through Croatia. Well, if you cut the Russian oil deliveries, then you rely on the on the very last and only remaining pipeline. But that pipeline has a lower capacity, way lower capacity compared to the demand of Hungary and Slovakia together.”

“So basically,” he added, “if someone would like to cut us from the Russian oil supplies, would end up in endangering the country’s energy supply simply because of physics.”

A similar situation exists as it relates to natural gas, the main supply of which now comes to Hungary from Russia via the TurkStream pipeline that connects Russia and Turkey. This route proved crucial in January as Kyiv refused to a renew a decades-long gas transit agreement with Moscow.

Ukraine has been tied to kinetic action as well, however, with Kyiv striking Russian infrastructure involved in carrying oil to European nations, such as Hungary, including in two incidents last month. Further complicating the situation, according to Szijjarto, have been added fees to the Croatia oil link and EU opposition to exploring alternative gas options in Qatar and Azerbaijan.

“So, the problem is that, on one hand, you are being pushed to get rid of the existing, reliable sources, but there’s no alternative,” Szijjarto said. “So, it would be totally different if they say, ‘Okay, guys, get out and you have option one, two, three,’ but there’s nothing.”

In fact, he explained, “the only Western politician whom I talked to in the last 11 years I’m in this position who said that, ‘Yes, geography must be respected,’ was Marco Rubio”—another sign of the robust ties between the Trump and Orban administrations.

Battle Between Budapest and Brussels

Divisions between Hungary and EU leadership run even deeper than opposing views on the war in Ukraine. The Brussels-based bloc has censured Budapest, freezing funds and demanding fines, over an array of domestic policies, including those relating to asylum-seekers and LGBTQ+ communities.

Here, too, Szijjarto sees an ally in Trump, referring to the Orban administration’s approach as “Hungary First” and “Make Hungary Great Again.” He calls the relationship between the nations, their leaders and outlooks “unique.”

“If you look at the major dilemmas facing the world and countries one by one, in all cases, basically we will look at the same way to solve them,” Szijjarto said, “so a very strong anti-migration policy, wall on the border, fence on the border, pro-family policies, pushing back this gender ideology, marriage between one man and one woman, mother is a woman, father is a man, supporting families, supporting peace to come, a patriotic, economic, political strategy, the role of Christianity to be respected.”

Through this lens, he said “the driving line of foreign policy is national interest.”

“And we always reject that intellectually pretty low approach, which says that you are pro-American, pro-Russian, pro-Chinese,” he said. “No, we are pro-Hungarian. And we have made it very clear that we are not ready to give up our specificities. We are not ready to give up our national identity. We are not ready to get rid of our history, culture, religious heritage. No way.”

“We are a Christian country for more than 1,000 years. We are proud of it, and we are not ready to melt this in a United States of Europe,” he added. “So, therefore, when it comes to the debates internally in the European Union, we are very clearly on the sovereignty side saying that, yes, the European Union must be strong, but it must be based on strong member states. So, we don’t want member states to be melted in a European Empire.”

Concerns over the emergence of such an “empire ruled from Brussels,” as Szijjarto phrased it, have also helped propel a number of conservative movements across the EU, including a rise of right-wing nationalist populist parties in the likes of Austria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Szijjarto refers to the historic wave of electoral victories of what he called “patriotic parties” across Europe as a natural reaction to a “very extremist liberal” agenda that had previously been taking root. At the same time, he felt established EU leaders were likely to take extreme measures to suppress the trend, including backing deals to sideline right-wing movements in countries like Austria and the Netherlands, or stirring up anti-government protests in Serbia.

In Hungary, too, Szijjarto said that “Brussels does everything in order to put a puppet government in our place in the next elections,” which are due to take place in April. He argued Hungary was paying the price for its independent stance.

“Hungary, as such, is an obstacle to this extreme liberal mainstream to overrule Europe,” Szijjarto said. “We are always the ones who say no. We are always the ones who put the spotlight on rationality and common sense, plus we prove that you can be successful while carrying out an anti-mainstream policy as well. And this is the most dangerous for this liberal mainstream, because what they say about themselves is that that’s the only progressive only successful way. “

“And with our existence that we are following a different strategy, but still being successful, that cannot be digested by them,” he added. “And therefore, they try to do everything in order to support those who are against us and who have a chance, they think at least, to throw us out from government.”

He referred to such actions as “threats,” that were being posed “very strongly” from Brussels to Budapest.

“Because this liberal mainstream and this extremist liberal approach have weakened Europe a lot recently,” Szijjarto said. “Just look at where Europe was when it comes to the political weigh and economic weight, and compared to that, we are very weak.”

“And this doesn’t happen out of scratch,” he added. “This happened because of bad decisions, because of mistakes, because of failures committed in and by Brussels.”

Looking East

But whereas Szijjarto emphasizes that Hungary remains a fully “committed” member of both the EU and NATO, he also says his nation could not ignore some of the opportunities emerging beyond the West.

“We see the reality,” Szijjarto said. “We see that when it comes to the global economy, the Eastern part of the world is dictating the speed in most of the critical industries, in most of the critical parts of the global economy. And we want to be part of the benefits. So, therefore, our strategy, economically speaking, is economic neutrality.”

The remarks are underscored by Orban’s “Eastern Opening” policy that has sought to channel Chinese and Russian investment, as well as historic roots in the East via Hungary’s observer status in the Organization of Turkic States. Orban was also one of two EU and NATO leaders, alongside Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico, to attend China’s recent victory parade marking 80 years since the end of World War II.

In an increasingly multipolar world where the traditional order is beset by crises, however, Szijjarto, who is also the country’s top trade official, said Hungary was far from alone in this maneuvering — even if it ultimately faced some of the most criticism for it.

“When I compete for Chinese investments, for example, then my competitors are always Western European countries,” Szijjarto said. “And those Western European countries usually complain about the heavy presence of Chinese capital in Europe once they lose these competitions, which is very hypocritical in this regard.”

“So, economic neutrality is a key factor of our strategy,” he added, “and we have taken a lot of benefit out of it.”

Read the full article here