On February 20, the Galápagos National Park Directorate and conservation partners released 158 giant tortoises on Floreana Island — the first time the species has roamed there in more than 150 years, after heavy hunting by whalers and the introduction of invasive predators wiped them out in the mid-1800s.

The release was guided by NASA satellite technology that helped scientists identify exactly where the animals would have the best chance of long-term survival.

Without Tortoises, an Ecosystem Fell Apart. Now They’re Back.

Giant tortoises weren’t just residents of Floreana — they were architects of it.

For centuries, they grazed vegetation, cleared pathways through dense plant growth, and dispersed seeds across the island. Their disappearance triggered an ecological collapse that reshaped the landscape over generations.

Restoring them isn’t symbolic. It’s structural. The tortoises are the keystone around which Floreana’s broader ecosystem can be rebuilt, and their return marks the most significant rewilding milestone the island has seen in modern history.

How NASA Satellites Told Scientists Exactly Where to Release the Tortoises

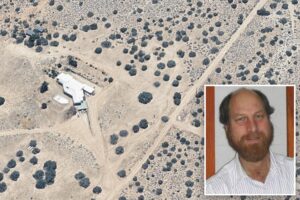

Tortoises released from captivity face an immediate problem: they have no instinct for where to find food, water, or nesting ground on an unfamiliar island. To solve this, researchers built a decision tool using data from multiple NASA satellite missions — including Landsat, the Global Precipitation Measurement mission, and the Terra satellite — to map vegetation, rainfall, temperature, and terrain conditions across Floreana.

That data was combined with millions of field observations of tortoise locations across the archipelago to produce habitat suitability maps, not just for today, but forecasted up to 40 years into the future. The long-range modeling matters because giant tortoises can live more than a century — meaning where the island’s climate and vegetation are headed is just as important as where they are now.

In 2000, researchers discovered unusual tortoises at Wolf Volcano on Isabela Island whose appearance didn’t match any known living species. DNA extracted from bones of the extinct Floreana tortoise later confirmed these animals carried Floreana ancestry — most likely because whalers moved tortoises between islands more than a century ago. A breeding program launched from that discovery produced the hundreds of offspring now being returned to Floreana.

The Galápagos National Park Directorate has released more than 10,000 tortoises across the archipelago over the past 60 years, making it one of the largest rewilding efforts ever attempted.

‘Charles Darwin Was One of the Last People to See Them There’

James Gibbs, Galápagos Conservancy Vice President of Science and Conservation: “It’s a huge deal to have these tortoises back on this island. Charles Darwin was one of the last people to see them there. If you can place them where conditions are already right, you give them a much better chance.”

Keith Gaddis, NASA Earth Action Biological Diversity and Ecological Forecasting program manager: “This is exactly the kind of project where NASA Earth observations make a difference. We’re helping partners answer a practical question: Where will these animals have the best chance to survive — not just today, but decades from now?”

Christian Sevilla, Director of Ecosystems, Galápagos National Park Directorate: “We move from intuition to precision. It demonstrates that large-scale ecological restoration is possible and that, with science and long-term commitment, we can recover an essential part of the archipelago’s natural heritage.”

11 More Species Are Waiting

Researchers will monitor the released tortoises to track how well they adapt to Floreana’s terrain and whether the satellite-selected release sites perform as modeled.

The tortoise release is the opening move in the broader Floreana Ecological Restoration Project, which also aims to eliminate invasive species — including rats and feral cats — and return 11 additional native animal species to the island.

The Galápagos Conservancy plans to expand the NASA-powered decision tool to guide future reintroductions across the archipelago. If Floreana succeeds, it could serve as a replicable blueprint for ecosystem restoration efforts far beyond the Galápagos.

Read the full article here