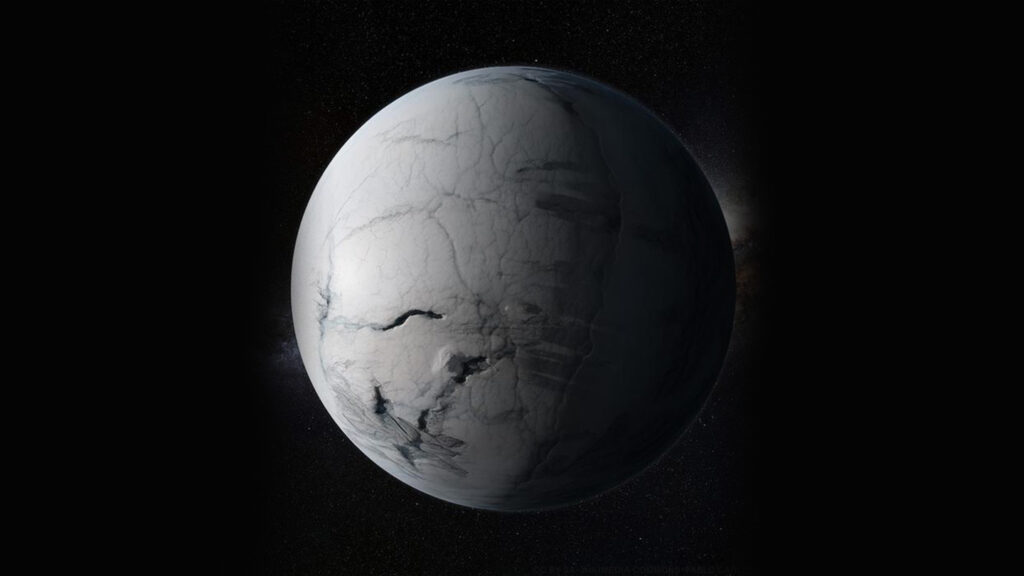

Over 600 million years ago, most of Earth completely froze over, becoming “Snowball Earth.” But even during this frigid period, the climate still behaved in familiar ways, earth scientist Chloe Griffin and colleagues report in the April 1 Earth and Planetary Science Letters. There even seems to have been a tropical climate cycle, like modern El Niños and La Niñas.

“Everyone thought that the climate system would be really quite stable due to global ice coverage,” says Griffin, of the University of Southampton in England. Instead, she and her colleagues found evidence of an active climate and a partially open ocean.

Earth experienced its first freezing spell about 2.4 billion years ago. Then, during the Cryogenian period about 720 to 635 million years ago, there were two Snowball Earth epochs. The first, the Sturtian glaciation, lasted from about 717 to 658 million years ago.

Griffin and her team studied Sturtian rocks from the Garvellach Islands, off the west coast of Scotland. The rocks contain beautifully preserved stacks of thin layers, alternating between coarse and fine sediments. This is unusual for rocks from the Cryogenian: Most are badly eroded and jumbled because glaciers tore them up.

Today, such layers are found under glacial lakes. Each summer, coarse sediments are carried into the lake by glacial meltwater. But during the winter, the meltwater ceases, so only fine clays are deposited. As a result, each year produces two distinct layers. This process, Griffin says, is what produced the Sturtian rocks. The rocks contain about 2,600 pairs of layers, meaning they recorded about 2,600 years.

It’s “unprecedented” to find annual records this far back in time, says study coauthor Thomas Gernon, an earth scientist also at the University of Southampton.

Each layer’s thickness hints at the weather conditions in that season. For example, a warm summer means more glacier movements and erosion, producing a thick layer of sediment. The researchers mathematically analyzed the thickness of the layers to look for patterns. They found four distinct cycles, repeating every 4 to 4.5 layers, 9 layers, 13.7 to 16.9 layers and 130 to 150 layers.

These all correspond to well-known modern-day climate cycles, assuming that the layers were laid down annually. The 4-to-4.5-year cycle most resembles the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, in which the tropical Pacific Ocean alternately releases heat into the atmosphere, creating El Niño conditions, and absorbs heat from the air, creating La Niña conditions. Griffin says her team’s findings reflect “some form of heat transport between an ocean and atmosphere occurring in the tropics,” which indicates there must have been some open ocean, probably near the equator.

The remaining three cycles seem to represent the sun’s intensity waxing and waning, the researchers concluded.

While it’s not possible to confirm that the layers were laid down year-by-year, it’s a reasonable interpretation, says geologist Tony Prave of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “You could go to a glacial lake in Switzerland, look at a core that’s taken out of that lake, and it’ll look exactly like what is preserved in the Garvellach Islands,” he says.

The findings feed into an ongoing dispute over the extent and severity of Snowball Earth and whether there were areas of open water. Data from around the world support a truly global glaciation, in which biogeochemical cycles were shut down and the oceans barely interacted with the atmosphere, Prave says. But sites like the Garvellach Islands point to a more dynamic climate.

The rocks may reflect a short-term warming, perhaps caused by volcanoes or asteroid impacts, Gernon suggests. While the layers span about 2,600 years, the Sturtian glaciation lasted 59 million, he says.

It’s also possible that the rocks date from either the beginning or the end of the Sturtian glaciation, when Earth was partly defrosted, Prave says.

Read the full article here