After a heart attack, the heart “talks” to the brain. And that conversation may make recovery worse.

Shutting down nerve cells that send messages from injured heart cells to the brain boosted the heart’s ability to pump and decreased scarring, experiments in mice show. Targeting inflammation in a part of the nervous system where those “damage” messages wind up also improved heart function and tissue repair, scientists report January 27 in Cell.

“This research is another great example highlighting that we cannot look at one organ and its disease in isolation,” says Wolfram Poller, an interventional cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the study. “And it opens the door to new therapeutic strategies and targets that go beyond the heart.”

Someone in the United States has a heart attack about every 40 seconds, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That adds up to about 805,000 people each year.

A heart attack is a mechanical problem caused by the obstruction of a coronary artery, usually by a blood clot. If the blockage lasts long enough, the affected cells may start to die. Heart attacks can have long-term effects such as a weakened heart, a reduced ability to pump blood, irregular heart rhythms, and a higher risk of heart failure or another heart attack.

Although experts knew from previous research that the nervous and immune systems could amplify inflammation and slow healing, the key players and pathways involved were unknown, says Vineet Augustine, a neurobiologist at the University of California, San Diego.

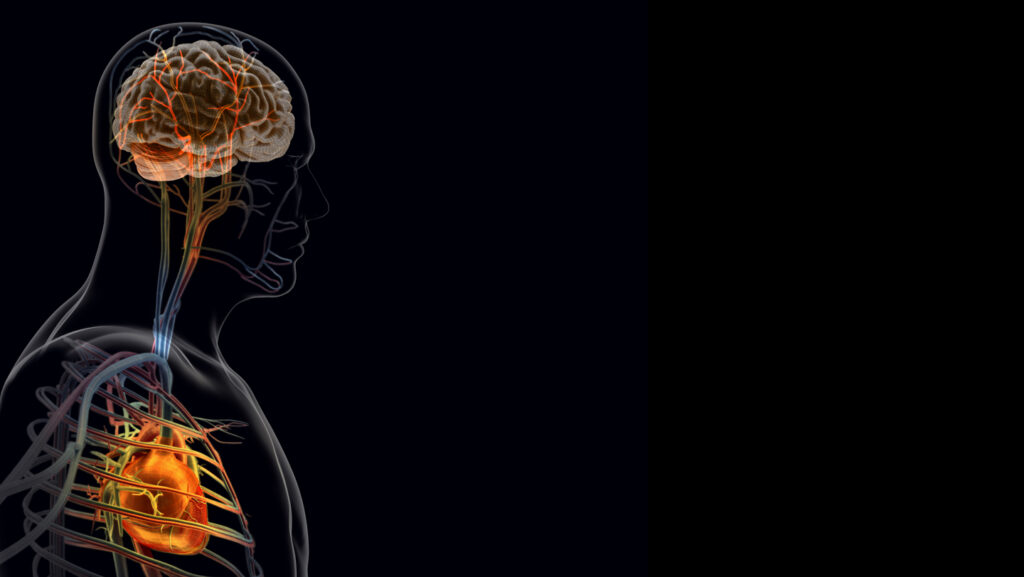

To identify them, Augustine and his colleagues began by pinpointing the sensory neurons that detect heart tissue injury. The team zeroed in on the vagus nerve, which carries sensory information from internal organs to the brain and identified a specific subtype of vagal sensory neurons, called TRPV-1 positive neurons, which extend into and sit next to heart tissue as key contributors in the brain-heart pathway. After a heart attack, more TRPV-1 positive nerve endings became active in the damaged area of the heart, experiments showed.

But when these neurons were shut down, cardiac pumping function, electrical stability scar size, and other measures of heart health improved. That bolsters evidence that the heart ramps up the signals it sends to the brain after a heart attack.

The team traced the path of those signals from the heart to the brain. Their first stop was the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, a region that helps control stress, blood pressure and heart rate. The signals then reached the superior cervical ganglion, a cluster of nerve cells in the neck that sends signals to organs such as the heart and blood vessels.

After a heart attack, the cluster of nerve cells in the neck appeared more inflamed, with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory molecules called cytokines. When the scientists reduced inflammation in this group of nerve cells, heart damage eased, and the team saw improvements in cardiac function and tissue repair.

It is important to note that “the inflammatory response is not inherently negative,” says Tania Zaglia, a physiologist at the University of Padua in Italy who was not involved in the study. “In the early phases of infarction, it is essential for the removal of damaged tissue and for the activation of reparative processes.” However, she says, problems arise when this response becomes excessive, prolonged or disorganized.

That’s why controlling the inflammation, as well as the nerves that may be driving it, could be beneficial, the researchers say. Taking the findings from mice to the clinic will take time. Still, “we can now start thinking about therapies such as vagus nerve stimulation, gene-based approaches targeting the brain or immune-targeted treatments,” Augustine says.

Read the full article here