Numerous daring rescues by raft, rope, boat and grit took place at places like Casterton, Coleraine, Byaduk, Koroit and Port Fairy.

More than a hundred bridges washed away. Drowned livestock piled against fences.

A home in Spring Gardens, Warrnambool, during the 1946 floods.Credit: State Library of Victoria

Five members of a single family, the Sparrows, perished in appalling circumstances near the town of Macarthur.

In and around engorged lowland, every fence post visible above the water was said to be crowned by a curled tiger snake.

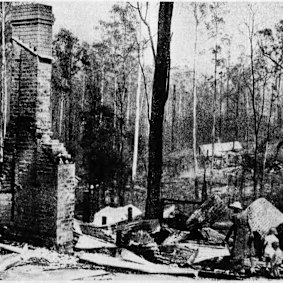

The Condah swamp, a vast wetland north of the Gunditjmara Aboriginal people’s ancient eel-trapping system on Tae Rak, known then as Lake Condah, had been drained unwisely in the 1880s.

Where once tens of thousands birds gathered – magpie geese, snipe, ibis, ducks and great flocks of brolgas, and where Aboriginal people were recorded at the time of European arrival living in substantial huts – became farmland.

A farmstead on the edge of Lake Condah, c. 1880.Credit: State Library of Victoria

As rain pelted down, the old drainage, which had fallen into disrepair during the Depression years of the 1930s, couldn’t cope.

The Condah swamp became an immense inland sea, three metres deep.

Edgar Lacey and his wife Amelia and their teenage daughter, Grace Tullett, found themselves trapped, their house an island.

Without food and freezing, they climbed atop their roof, removed a sheet of roofing iron and squeezed into the ceiling space.

Eventually, the rising water robbed them even of this flimsy mercy. They were forced out to sit astride the pitched roof, sharing their perch with snakes and a waterhen.

And the crew of a great flying boat, trained to find and rescue shot-down air crews across the endless Pacific, could not help them.

The capricious nature of Victoria’s environment, weather and climate was on extravagant display.

As Victorians began this week to count the loss and the cost caused by the latest disaster – this time, grass fires and bushfires – it was possible to overlook the misery of the state’s other regular calamity: flood.

The historical record reveals major bushfires occur in combustible Victoria about every four years, and sometimes more frequently.

The flooded streets of Casterton, south-west Victoria, in March 1946.Credit: State Library of Victoria

Flood can be expected somewhere in the state almost every year.

Whatever the arguments about what was the worst, the biggest, the most destructive, every fire and flood is traumatic to those who lose family, friends, houses, farms and livestock.

Though we cannot predict the next calamity, we can be sure it is coming.

Loading

Extreme fire weather days have increased in Australia by 56 per cent over the past four decades, according to research by an international team of scientists, including Australia’s CSIRO.

Climate change, in short, is driving ever-increasing risks, and anyone taking notice knows the world is failing to reduce carbon emissions at anywhere near the rate required.

We can, however, look back decades, back before climate change was part of the conversation, to wonder how much worse things might get.

Among the near-forgotten years of drought, fire and flood in Victoria were those of the 1940s, during World War II.

The ruins of a home at Big Pat’s Creek.Credit: The Age Archives

They remain overshadowed by the horror of Black Friday, when fires reached their crescendo on Friday, January 13, 1939, burning 1.5 to 2 million hectares of farmland and forests, killing 71 people and destroying whole villages.

My own great-grandfather, fleeing the flames after failing to save his family’s house, caught his foot in a fence and was cruelly burned that day.

But as war descended and Australians sailed away to fight in the Middle East, Europe, South-East Asia and the Pacific, drought spread across Victoria.

The dry brought more fire, and there weren’t enough experienced firefighters left to face it down.

Catastrophe blew in on a hot December wind near Wangaratta in 1943. Volunteers who rushed to fight the fire on December 22 were trapped by a wind change at a rural spot known as Tarrawingee. Five of the group, including two 14-year-old schoolboys, died at the scene. Another five men died in hospital soon after.

Shock was profound.

Within weeks, Victorians reeled again as fire raced through grassland in the Western District, destroyed more than 500 houses, roared down Mount Sturgeon and burned much of Dunkeld to the ground, and encircled Hamilton, Skipton and Lake Bolac. About 20 people died as 440,000 hectares burned in eight hours.

Later that year, more fires caused destruction and loss of lives around Yallourn, the loss of power generation threatening Australia’s war effort.

The Victorian government was forced to take action. It legislated in late 1944 to establish Victoria’s first unified, statewide rural firefighting body: the Country Fire Authority.

Loading

These years later, the CFA remains the state’s army of volunteers and professional firefighters who perform acts of bravery equal to any on a battlefield when the worst happens, just as many of them did last weekend.

World War II ended in August 1945. The deeply wearied population breathed easier, believing everyone was due for a break.

But Victoria’s mercurial nature had yet another stupefaction to serve up.

If Black Friday was one bookend to the war years, and the fires of 1943-44 were the great disasters of the home front, the Big Flood of March 1946 was the closing act for the people of far south-west Victoria.

As emergencies engulfed every community with a creek, a river or a swamp, word spread of the Lacey family’s lonely plight.

There was no state emergency service with fancy equipment for water rescue.

But no one was about to look away.

Soldiers and airmen back from the war knew there were still Catalina flying boats operating. The RAAF responded.

A Catalina out of NSW was diverted to Lake Condah.

Loading

Relief turned to despair when the weather’s murk rendered the mission impossible.

Still no one surrendered.

A small flat-bottomed boat was launched. The choppy floodwaters were too much for it.

Elsewhere around the district, the army brought in amphibious vehicles known as Ducks (DUKWs, used during the war to transport troops and supplies) to rescue stranded citizens. But the demands from populated areas came ahead of remote Lake Condah.

Word of the crisis reached Portland’s professional fishermen.

The Fredericks brothers, Charles and Alf, members of a well-known fishing family in the old port town, couldn’t turn away, though Portland itself was flooded.

They hauled their boat out of the sea, loaded it on to a heavy truck and headed 50 kilometres north through swollen creeks, sheets of water and mud.

Accompanying them were a Portland policeman, First Constable G.F. Lang, and the constable from nearby Heywood, Fred Stehn.

Eventually, they unloaded the boat with help from locals late at night and set off into the Condah swamp, its waters thick with weed and debris, making the motorboat’s propeller useless.

The Fredericks men rowed for more than an hour and reached the Lacey house, only the peak of its roof visible, at 5.30am.

The family was suffering exposure and exhaustion so deep, their rescuers related, they were unable to feed themselves when they were taken into the boat.

As the Fredericks men pulled at the oars, mission accomplished, they looked back to see the old house collapsing into the floodwaters.

As the Fredericks men pulled at the oars, mission accomplished, they looked back to see the old house collapsing into the floodwaters.

The Fredericks brothers, the two policemen and another Portland fisherman, George Jennings, were all awarded silver medals for heroism by the Royal Humane Society.

Altogether, 21 such medals were awarded to rescuers across south-west Victoria, and another five received bronze medals.

Loading

North-west of the Condah swamp, at another drained wetland, Buckley’s Swamp, the Big Flood finally doused a peat fire that had been burning ever since 1944.

A few days later, March 20, a boy named Graeme was born to the family of Joe Wallis, who had tried to direct a flying boat towards the stranded Laceys.

In the bush, you help your neighbours. Life goes on.

Read the full article here