A new diagnostic device that uses a blood test to understand messages in the brain could revolutionise the way one of Australia’s deadliest cancers is treated, according to doctors from the University of Queensland.

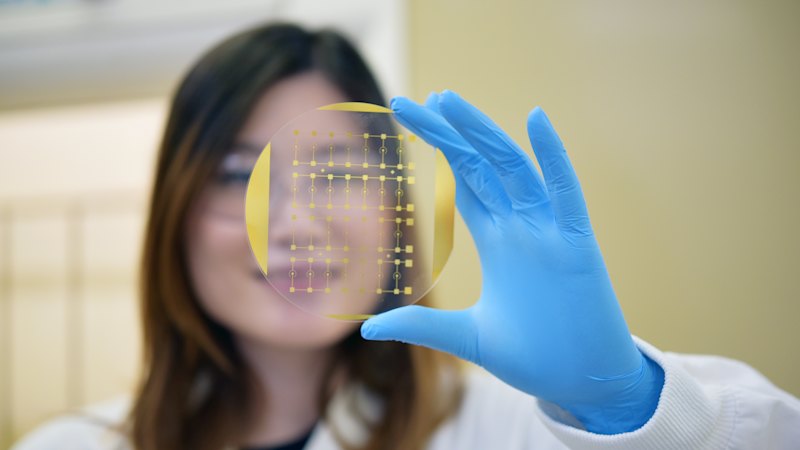

The device – called a Phenotype Analyzer Chip – reads how glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, responds to treatment, potentially removing the need for invasive procedures and improving survival rates.

Dr Richard Lobb and Dr Zhen Zhang from UQ’s Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology called it “a window to the brain”, requiring little more than a non-invasive blood sample to get “fast and accurate information” on the cancer.

“What we’ve been trying to do is develop a blood test that reflects what’s happening biologically in the brain in real time … to really understand whether that treatment is being effective or not,” Lobb said.

Lobb’s background looks at how cells communicate, and it’s on this basis that the device functions.

“I work on what’s called extracellular vesicles. You can think of these as essentially text messages sent by cells,” he said.

“They’re small, but they carry a lot of meaningful information about what’s happening inside cells or, for example, what’s happening inside the brain.”

The chip works by examining small samples of blood and capturing messenger cells (extracellular vesicles) that originate from glioblastoma tumour tissue.

“These particles cross the blood brain barrier laden with information on the disease, and with our hypersensitive device we can pick them up and interrogate them,” Zhang said.

Last year, around 1640 people died from brian cancer and more than 2000 new diagnoses were recorded.

Glioblastoma is the most common form of brain cancer in Australia, and is considered particularly deadly because of its delicate location, aggressive growth and challenges with accurately monitoring treatments.

“There has been very little success so far in clinical trials for new and experimental glioblastoma treatments,” Lobb said.

“That’s partly because there is no way to tell if a therapy is working precisely as it should at that moment without drilling into someone’s head.”

While the device wouldn’t replace the need for some invasive procedures – such as an MRI scan and biopsy to diagnose the tumour – it could improve treatment outcomes, particularly for patients in remote and rural areas.

“Even when an MRI scan does show that there is a change, it can be unclear whether the tumour is growing or if the brain is simply reacting to the therapy,” Lobb said.

“That uncertainty can be very stressful for patients and families, and sometimes the only definitive option is to go in for another brain biopsy that carries risk and can’t be done often.”

The device has been validated in more than 40 brain cancer patients and will be implemented in clinical trials with support.

Lobb hopes to see it used to unlock therapies for other neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s and motor neurone disease in the future.

“If we can capture and analyse the right extracellular vesicles in a patient’s blood, we can get new information about the onset and mechanism of progression of a wide range of brain diseases.

“Glioblastoma really is just the beginning for this technology.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

From our partners

Read the full article here