Last month, the U.S. government officially launched a new—and controversial—immigration program called the “gold card” visa initiative. Designed to replace or improve upon existing investor-based visa paths (notably the EB-5 visa, which grants a green card to foreign investors who invest and create jobs in a U.S. business), the gold card provides wealthy foreign nationals with a fast track to U.S. permanent residency—and potentially citizenship—in exchange for a significant financial investment.

In addition to the gold card, the government has also proposed a platinum card, aimed at high-net-worth individuals seeking more generous residency privileges and favorable tax treatment.

While the two programs share a common objective—to attract global capital into the U.S.—they differ significantly in cost, tax implications, and intended beneficiaries.

These options are intended to encourage foreign nationals with significant assets who are looking for quick and efficient paths to U.S. residency—and potentially advantageous tax benefits. It’s likely that the visas will attract individuals from countries that are currently experiencing backlogs in employment-based immigration categories, like China or India, or those who are finding traditional immigration pathways burdensome.

Gold And Platinum Card Programs

Ronnie Fieldstone, the chair of the global immigration and financial investment practice at Saul Ewing LLP, has experience in facilitating immigration and investment across international boundaries. Fieldstone notes that the firm has managed over 500 EB-5 projects, collectively raising more than $9 billion in capital through the EB-5 program—so he knows a little something about investment-based programs.

Fieldstone explains that the gold card program allows foreign persons to obtain a visa by making a payment to the U.S. government—$1 million for individuals, or $2 million if the payment comes from a corporation, such as the individual’s employer. (It remains unclear whether derivatives—meaning a spouse and children under 21—are included under a single petition. While the program builds on an existing visa structure that includes derivatives, the Executive Order touting the gold card specifies that the $1 million payment is per person.)

David Shapiro serves as Chair of Saul Ewing’s tax practice, where he focuses primarily on transactional and tax planning matters, particularly those involving family businesses and investors relocating or investing across borders. He adds that the platinum card would function similarly but at a higher price point—$5 million. Because of its proposed tax benefits (more on that later), the platinum card would likely require Congressional approval before it could be implemented.

Ideal and Not-So-Ideal Candidates

Who would be a good candidate for these programs? According to Fieldstone, the gold card may appeal to individuals who would otherwise pursue EB-1 or EB-2 visas but face lengthy backlogs due to retrogression, particularly applicants from countries such as China and India. It’s not clear, he says, whether any pending applicants for EB-1 and EB-2 residency programs are grandfathered or whether they could convert their applications to gold card programs.

(EB-1 visas are targeted to those with extraordinary abilities in some fields, sometimes referred to as an “Einstein visa” while EB-2 visas typically focused on those with advanced degrees.)

As for the platinum card, Shapiro notes that it would be most attractive to individuals who hold significant non-U.S. assets—particularly business interests that would otherwise be heavily taxed or require substantial compliance efforts if the individual were deemed a U.S. tax resident.

These programs clearly aren’t suitable for everyone. They require money paid up front and carry some potential tax consequences. Shapiro points out that makes participation ultimately a personal decision. Additionally, because the required payment represents a direct transfer to the U.S. government rather than an investment, he says that applicants should consider the long-term costs compared to other visa options.

Tax Residency Implications

Neither the gold nor the platinum card automatically establishes U.S. tax residency. Shapiro explains that gold card holders could become U.S. tax residents based on the substantial presence test. Here’s how the test works: you count the days that you were present in the U.S. in the current year, 1/3 of the days spent in the U.S. in the prior year, and 1/6 of the days spent in the U.S. in the year before that—if this total equals or exceeds 183 days, you are treated as a U.S. tax resident. Notably, the test does not depend on the kind of residence you establish, your intentions of returning to the U.S., or the nature and purpose of your stay abroad. (That tests apply generally to tax residency—it’s not a quirk of the gold card.)

However, if you are a resident in a country with which the U.S. has a tax treaty, you could potentially rely on the treaty to assert that you are not a U.S. tax resident, even if you would otherwise be treated as a resident under the physical presence test. Fortunately, there are more than 60 countries with a U.S. tax treaty.

The platinum card would allow individuals to enter the U.S. for up to 270 days per year without becoming a tax resident, Shapiro says—but any longer than that could trigger U.S. tax residence under the substantial presence test (subject to potential tax treaty application, as with the gold card). Even if a platinum card holder is not a tax resident, they would be subject to U.S. taxation on U.S. source income. Because this is a significant change from current federal law, he says, “we believe that Congressional action will be required to implement the platinum card as proposed.”

Assets For Investment

The cards are framed in terms of usefulness for investment purposes. However, Fieldstone clarifies that the current administration appears to treat the payments made under these programs as investments in the United States—specifically as contributions to government operations. And unlike EB-5 investments, these payments do not produce economic returns or involve recoverable capital—they are straightforward transfers to the federal government.

So what assets might be used to fund these payments? So far, there’s not a lot of guidance, including sourcing. Fieldstone suggests that investors will likely be vetted for the source of their funds during the qualification process.

Most likely, when it comes to kinds of assets, cash is king. Some attorneys have already warned taxpayers away from using other assets, like self-directed IRAs for investment (arguing that it might violate section 4975, which generally imposes excise taxes on prohibited transactions involving tax-advantaged retirement plans, to prevent misuse of the plan’s assets for personal gain). Shapiro generally agrees because of the prohibition on private benefit.

Legislative Considerations And Timing

Ready to sign up? Not so fast.

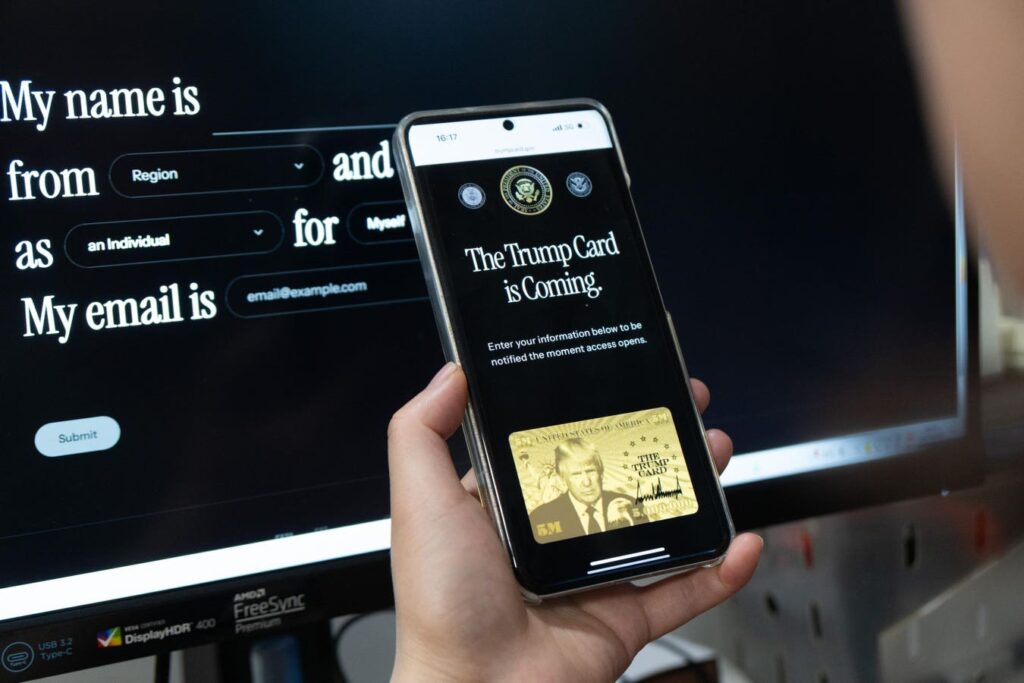

While the current website (trumpcard.gov) promises that “For a processing fee and, after DHS vetting, a $1 million contribution, receive U.S. residency in record time with the Trump Gold Card,” you can only “Sign up now and secure your place on the waiting list for the Trump Platinum Card.”

As of now, Congress hasn’t authorized the proposed tax provisions associated with these programs. With Congress currently focused on the government shutdown, there is uncertainty about when—or whether—such measures might pass. If a consensus cannot be reached, the proposal may have to wait until the next budget bill is passed.

Read the full article here