When new dietary guidelines for Americans came out in early January, I couldn’t help but notice “healthy fats” at the top of the inverted food pyramid.

Like the food pyramid itself, the new guidelines have upended previous nutrition advice, which favored fats from plants over those from animals. Now the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services list butter, beef tallow and olive oil as examples of healthy fats.

Not so fast, say nutrition experts.

Most are on board with olive oil. It is neutral when it comes to heart disease, says Marion Nestle, a professor emerita of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University.

But telling people to use saturated fats like butter and other animal fats in place of plant-based unsaturated fats, such as those found in vegetable or seed oils? That goes against years of health research, says Deirdre Tobias, a nutritional epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Epidemiological studies and long-term clinical trials have conclusively shown that when polyunsaturated fats are eaten instead of saturated fats, “you get the biggest bang for your buck in terms of lowering risk of heart disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes [and] all-cause mortality,” says Tobias, who was on the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.

That committee issued a scientific report in December 2024 that did not contain the emphasis on meat and dairy. Usually, guidelines are based on the advisory committee’s report. Not this time. Instead, the agencies provided brief “Scientific Foundation” documents put together by a different group of advisers, some with ties to the meat and dairy industries. The potential health consequences of adding unhealthy fats to the diet “is what was most concerning about this swap,” Tobias says.

The focus on fat also ignores the fact that when people stop eating one thing, they substitute it with another, says Kevin Klatt, a registered dietitian and nutrition scientist at the University of Toronto. He worries that people who follow the message to eat more protein and full-fat dairy will reduce fiber intake and miss out on other essential nutrients in fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

I talked with these experts to get you the skinny on fats.

What are fats?

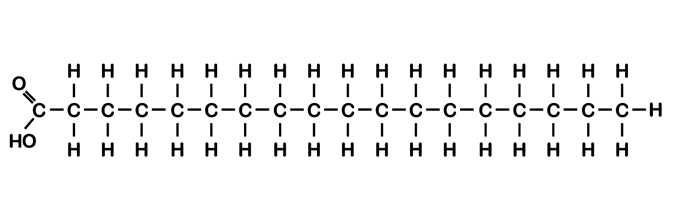

Let’s dive into the chemistry. Fats, or more accurately fatty acids, are molecules composed of long chains of carbon with some hydrogens and oxygen attached.

They come in several varieties. There are saturated fats. They are called saturated because every carbon in the chain has all of its potential chemical bonds filled, or saturated. These fats, such as lard, butter, coconut oil, palm oil and beef tallow are solid at room temperature.

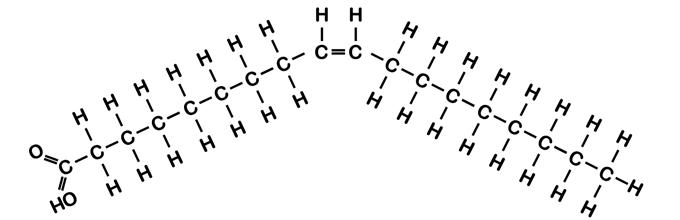

Then there are unsaturated fats. Those have one or more double bonds between carbons in the chain. A double bond introduces a kink in the chain, which prevents the molecules from packing in an orderly fashion. Unsaturated fats are usually liquid oils at room temperature.

Within unsaturated fats are monounsaturated fats. Those have one double bond in the chain. Oleic acid found in olive oil is a good example. Polyunsaturated fats have two or more double bonds. Fish, nuts and seeds are good sources of those fatty acids, which include omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

What do fats do in the body?

Here’s where it gets real for many of us. Fats have many functions. They form membranes around cells and organelles. Without fats, life may still be at the primordial goo stage.

Fatty acids are important messengers. The shape of the molecule, the length of the chain and other properties of fats are clues that help the body decipher instructions. Such messages are important for brain and immune function.

And fats store energy and nutrients, including some vitamins, and cushion internal organs.

Why do we need fat in our diet?

Our bodies don’t make all the fats we need.

“From a nutritional standpoint, you require fat in the diet because you need two different fatty acids, linoleic acid and linolenic acid,” Nestle says. Those two fatty acids come only from the diet. “You don’t need a lot of them,” but those fats are building blocks for other fats.

Nuts, seeds, legumes, eggs and meat are sources of linoleic acid, which is one of the omega-6 fatty acids. Omega-6 means that first double bond is located at the sixth carbon from the end of the molecule.

Fish, seafood, seeds and leafy green vegetables are sources of alpha-linolenic acid, the essential member of the omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 means the first double bond comes at the third carbon from the end. Both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids are polyunsaturated.

No natural fats are purely one type, Nestle says. “Fats that come in food are mixtures of saturated, unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. They are all mixtures. The only thing that varies is the proportion.” Meat and dairy fats and palm and coconut oils lean more heavily to saturated fat while vegetable and seed oils, especially flax seed oil, tend to contain more polyunsaturated fats.

Are saturated fats healthy?

Not really.

Nutrition research has generally shown that eating more saturated fat is associated with higher levels of low-density lipoprotein, LDL, also known as “bad cholesterol,” Klatt says. That type of cholesterol has been associated with a higher risk of heart attacks and strokes. Previous guidelines have used such links to chronic disease to recommend monounsaturated fats, like those in olive oil, or polyunsaturated fats, like canola or soybean oil, as healthier alternatives to butter or other animal fats.

Klatt and colleagues did a review of studies that examined the effects of reducing saturated fats in the diet or of replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats. The results were interesting.

For people at low risk of cardiovascular disease, cutting saturated fats had a statistically unimportant effect, the researchers reported December 16 in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Over five years, there was an estimated 1 less death per 1,000 participants who ate little saturated fat than among those who ate lots.

But for people at high risk — those with high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, diabetes, people who smoke or those who had previous heart attacks — lower saturated fat intake was associated with 6 fewer deaths and 12 fewer nonfatal heart attacks per 1,000 study participants, a statistically important reduction. And those with a high risk fared even better if they replaced saturated fats with polyunsaturated ones. About 21 fewer nonfatal heart attacks per 1,000 participants happened with that swap.

But nutrition research is difficult because scientists can never really tell what people are eating and whether they are swapping fats for sugar or other less healthy foods. “We don’t keep people trapped in a metabolic ward for five years and tightly control their diet,” Klatt says. “You can’t put it in a pill and randomize people [to eat] fat or placebo.”

How do calories fit into the picture?

Calories count.

Past dietary recommendations have advised limiting fat consumption not just for specific health reasons, but also to cut down on the number of calories people consume.

“All fats, across the board, whether saturated, unsaturated or polyunsaturated, have 120 calories per tablespoon. So the idea that you should go easy on fat comes from the fact that they have nine calories per gram,” Nestle says. That’s twice as many calories as in proteins or carbohydrates. “If you eat a lot of fat, you’ve got to reduce your calories someplace else.”

The current guidelines advise limiting saturated fat intake to no more than 10 percent of daily calories. That’s in keeping with previous recommendations. But new advice to eat more meat and full-fat dairy makes it difficult to stick to that limit, Klatt says. That’s a problem because previous guidelines that recommended nonfat or low-fat dairy products and plant-based diets gave more latitude to get nutrients while keeping calories in check.

For instance, “when you skim a milk and take out the fat calories, you leave all the protein, you leave all the calcium. You’re keeping all the essential nutrients, but now you just have fewer calories, and so that gives you a lot more to work with in a dietary pattern,” Klatt says.

“Saturated fats are nonessential fats. You don’t need them to survive,” he says. Human bodies already make all the saturated fat people need. In the diet, “all they do is raise [cardiovascular risk] and add calories without really adding much else.”

Are seed oils healthy?

Relative to saturated fats, yes.

Seed oils such as soy, canola and flax are conspicuously absent from the dietary guidelines, Klatt says. Previous dietary guidelines suggested using seed or vegetable oils in small amounts for cooking or in dressing and sauces. Seed oils tend to have a high ratio of polyunsaturated fats in relation to monounsaturated or saturated fat, and are rich sources of the two essential fatty acids

Polyunsaturated fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids, have been associated with better health outcomes than other types of fats. In short-term studies, replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats has been associated with lower LDL levels (often called “bad cholesterol”). And longer-term studies have found that people with more polyunsaturated than saturated fats in their diets tend to have fewer heart health problems.

But seed oils have gotten a bad rap lately.

Guilt by association with fried or ultraprocessed foods may be partially to blame, Nestle says. “Consumption of seed oils rose in parallel with the rise in prevalence of obesity between 1980 and 2000. But that’s association, not necessarily causation, because people started eating more of everything during that period, not just seed oil.”

What about the chemistry of seed oils?

Chemistry may play into seed oils’ recent vilification, Klatt says.

Some seed oils have a higher ratio of omega-6 linoleic acid to omega-3 fatty acids. In the body, linoleic acid gets converted to arachidonic acid, which helps promote inflammation. Inflammation plays a role in many chronic health problems, but is also necessary for wound healing and fighting infections.

But there’s not a direct dietary cause and effect. “Simply eating more linoleic acid doesn’t lead your cell membranes to become more rich in arachidonic acid,” Klatt says. That’s because the body regulates both the production of arachidonic acid and inflammation caused by it. So if a person eats more linoleic acid, the body will just dial back production of arachidonic acid, he says.

Another reason people worry about omega-6 fatty acids is because they compete with omega-3s for enzymes that elongate fatty acids into other important fats. Some people worry that consuming more omega-6 fatty acids could interfere with production of longer omega-3s, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA).

Klatt has a solution for that: Eat more fish. Fish are already rich in DHA and EPA so “you don’t have to worry about your body making its own from the plant-based precursors that you get in soybean and canola oil.”

Even if one type of seed oil contains a more favorable ratio of omega-3s to omega-6 fatty acids, Tobias says, “it doesn’t make the other one unhealthy, because they’re all healthier than butter and tallow.”

After chewing the fat with nutrition experts, I decided I’m sticking with skim milk. And I’ll continue using olive oil and fish as my fatty acid sources. That way, I don’t increase calories while trying to get the essential fats my body needs.

Read the full article here